Nothings Lasts Forever and Oddball Dystopias of the 70s and 80s

By Dominic Ellis

Nothing Lasts Forever, Saturday Night Live alumni Tom Schiller’s only feature film, barely lasted a day. According to film folklore, Schiller’s sci-fi comedy felt the wrath of unfavourable test screenings and was promptly canned by MGM in 1984. Despite having all the makings of a mainstream hit, with a star-studded cast including Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd, a Howard Shore score and an invite to Cannes, it was deemed too weird – too ‘out there’ – for a general public who had just got their first fix of Ivan Reitman’s Ghostbusters.

Nothing Lasts Forever eventually surfaced on European late night television in the mid-90s but has largely flown under the critical radar, bar a few festival appearances and occasional allusions to a ‘forgotten Bill Murray movie’. Which makes it all the more surprising that it is such a uniquely effective film.

Schiller piggybacked on a major film studio to create a biting sci-fi satire – an absurdist’s amplification of consumer culture and art set in a world where old folks are flown to the moon for shopping sprees and aspiring artists undertake state-run classical drawing tests. It’s silly and satirical in a way that’s symptomatic of a sci-fi sub-genre that flourished in the 1980s but is often overlooked in favour of the box office-dominating spectacle-based blockbusters.

Sleeper (Woody Allen, 1973)

Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher inspired a generation of cunning satirists who envisioned dystopian landscapes, Schiller among them. These filmmakers reanimated the bleak futuristic settings of George Orwell, Aldous Huxley and Ray Bradbury with farcical twists. Woody Allen’s Sleeper (1973) pre-empted this movement a few years before Reagan, fusing Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933) with THX 1138 (George Lucas, 1971). Adapting a familiar 50s B-movie concept now familiar to fans of Matt Groening’s Futurama (1999 - 2003), it injected slapstick humour and a distinctive retro-futuristic sense of place.

Miles Monroe (Allen) wakes up in a 22nd century police-state made up of elliptical architecture and doused in cold whites and greys. Slapstick-and-chase ensue, as every newly introduced technology is fraught with impracticality: the automated sex machine (“the orgasmatron”), the loveless robo-dog and genetically enlarged fruit. When we finally catch a semblance of colour in this taciturn dystopia, it comes in the form of McDonalds’ imposing golden arches. Allen showed that the future lends itself not just to dry political satire, but old-school screwball comedy, making for arguably his funniest film.

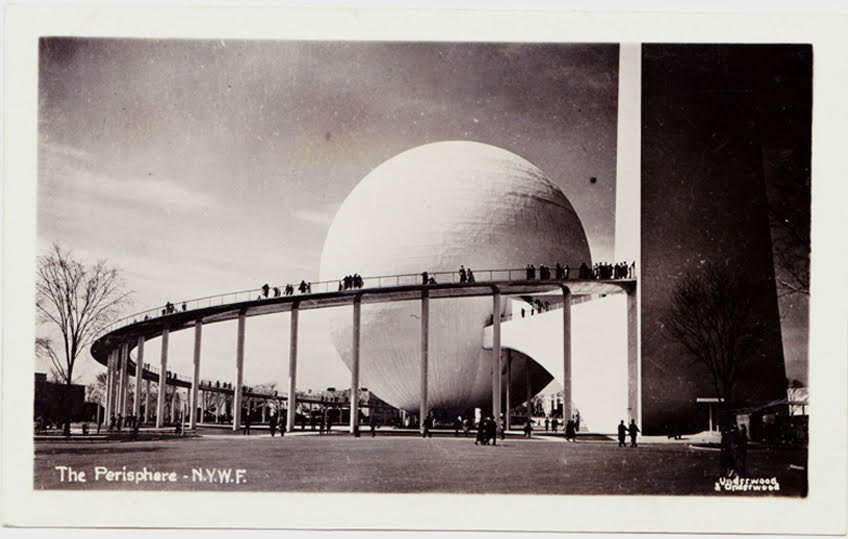

The 1939 New York World's Fair

Sleeper’s retro-futurism also showed that films of this genre rarely exist solely in the future. Allen envisioned ‘yesterday’s tomorrow’ with its architectural blueprint seemingly airlifted from the 1939 New York World's Fair (above). These cross-generational dystopias borrow aesthetically and thematically from the past to tell stories about the future, evoking an eerie nostalgia. Nothing Lasts Forever does something similar. Mostly shot in grainy black and white, with credits, transitions and various visual cues that closely resemble 40s and 50s cinema. “How the hell did I wind up singing on a bus to the moon”, remarks Eddie Fisher, an ageing icon of the 1950s, knowingly playing himself.

While Schiller’s weirdness was quickly shut down by the studio system, Terry Gilliam had enough sway to get his opus Brazil on the big screen, with a sizeable budget to boot. Despite being the most contemporarily renowned dystopian comedy, it was a commercial failure upon release, struggling to garner the same hype as fellow 1985 sci-fi alumni Back to the Future and Cocoon, directed by Robert Zemeckis and Ron Howard respectively. Sure, it had the scale and explosiveness of the spectacle-based sci-fi of the era, but vulgar stretched-out faces, mechanical angels and whimsical Samba made for confusing imagery – it simply wasn’t a very marketable film.

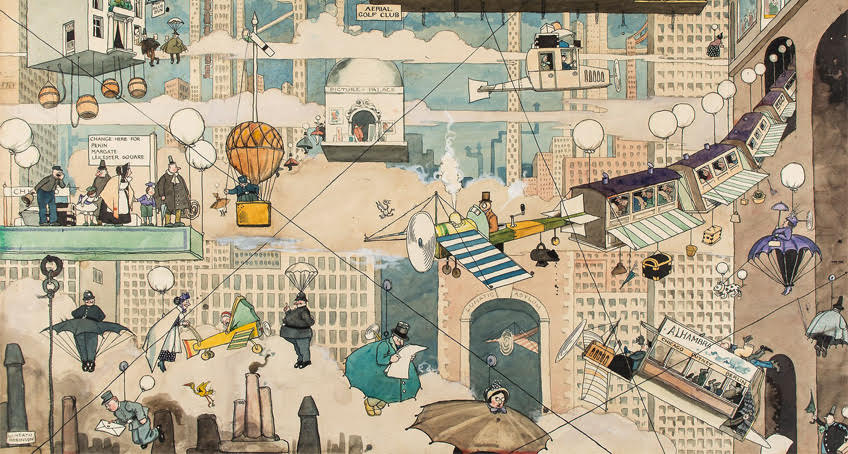

The illustrations of W. Heath Robinson

And yet, the effectiveness of Gilliam’s satire is predicated on this chaos. Brazil wears its hodgepodge influences on its sleeves. At one stage titled 1984½, Brazil takes narrative inspiration from Orwell and visual inspiration from Fritz Lang and film noir, also preserving Gilliam’s Monty Python stylings – as when two office-workers tussle over a table. Gilliam moulded an automated, bureaucratic world where nothing actually works, packing it with ineffectual domestic technologies akin to Allen’s robodog or Schiller’s impractically small portable TVs. In that sense, Brazil also pays homage to the early 20th century illustrations of W. Heath Robinson (above). Critic Michael Atkinson remarked that Gilliam turned retrofuturism into a “coherent, comic aesthetic” – coherent, paradoxically, in its anachronistic chaos.

Classic dystopian fiction is the backbone of most of these films

While classic dystopian fiction is the backbone of most of these films, none are more indebted than the little-known TV movie Between Time and Timbuktu (Fred Barzyk, 1972). Written by Kurt Vonnegut, it served as a sort-of adaptation of his 1959 novel The Sirens of Titan mixed with other bits and pieces from his literary canon. Less conventionally ‘dystopic’, it sagas the travels of Stony Stevenson, a “regular citizen” who inadvertently wins the opportunity to travel solo through space. “I think we’re typical Americans: his father committed suicide, I’ve been married three times”, Stony’s mother tells the press. Stevenson finds himself in the "Chrono-Synclastic Infundibulum” – a psychedelic mishmash of Vonnegutian landscapes – and madness ensues, making way for a cameo by a telepathic Hitler. Like Nothing Lasts Forever, it’s a buried relic, unbeknownst to all but the most loyal Vonnegut fans, and yet utterly unique in its subversive humour.

Nothing Lasts Forever is characteristic of a type of filmmaking that saw the future as a canvas for comic absurdity.

Another 1984 production, Sexmission (1983) is the rare 80s dystopia that was a commercial hit, beloved in Poland to this day. Noted satirist Juliusz Machulski is renowned for ridiculing his communist-ruled homeland, and Sexmission presents his woes through the lens of a post-apocalyptic matriarchy where men have been more-or-less written out of history. To the dismay of the female leaders, male scientists Max and Albert find themselves freed in 2044 after a failed human hibernation experiment and must escape a bunker before being subjected to “naturalisation” (sex reassignment surgery). Machulski’s world is one of provocative imagery but also senseless frat humour, making for a problematic allegory. While it’s hard to look past its blatant misogyny, Sexmission is innovative in its chamber piece approach.

As the world moved towards 1984 – both temporally and politically – Nothing Lasts Forever is characteristic of a type of filmmaking that saw the future as a canvas for comic absurdity, taking the foundational pieces of fiction and distorting them to their liking. As it happens, these buried time capsules have proven more far-sighted than dismissive audiences might have imagined, and deserve to be unearthed.

Nothing Lasts Forever plays as part of the Sci-Fi Marathon at The Astor Theatre on 12 August.