Remembering the Radical: An Interview with John Hughes

Critics Campus 2022 participant Digby Houghton speaks to Senses of Cinema co-director John Hughes about subversion, collective filmmaking and historiography.

I arrive at the State Library café around the same time as John Hughes, but he decides to sit in the smokers’ area outside while not smoking. I realise that I shouldn’t feel strange about such quirky decisions from the director of Senses of Cinema, a documentary about the radical 1960s and 70s film cooperatives that existed in Melbourne and Sydney. According to Hughes, who previously helmed Indonesia Calling (MIFF Premiere Fund 2009), a project like this – on which he collaborated with director/producer Tom Zubrycki (Ablaze, MIFF Premiere Fund 2021) since 2010 – is important in order “to remember a moment of insurgency”. Hughes’s honesty, emulated from the screen to his real-life persona, is inspiring; he tells me that “the organisational form of the co-op itself is something which needs to be remembered because we really need alternatives to capitalist modes of making things and sharing things”.

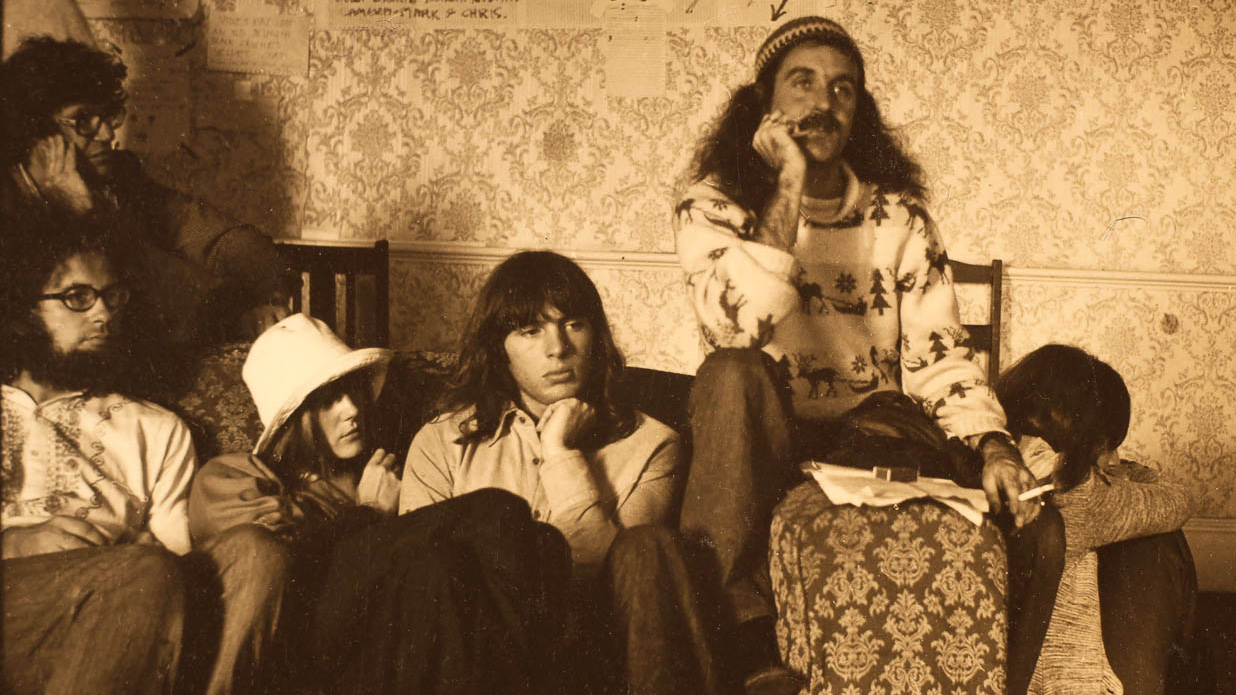

As a young film student writing my Honours thesis on Australian cinema from the 1970s, I find that Hughes’s documentary updates the relevance of the filmmaker co-ops for a new audience and refreshes the minds of those who lived through the turmoil. The co-ops were initially designed by unconventional filmmakers like Aggy Read, Albie Thoms, David Perry and John Clark, who maintained the Ubu Films collective; this group was named after the French absurdist play Ubu Roi from the turn of the century, which struck a nerve with the group. Hughes illustrates these artists’ early work through archival footage of films like Bluto (1967) and Boobs a Lot (1968), which experimented with form and medium. Thoms speaks about how Marinetti (1969) championed the dual-layered soundtrack in order to disorient the viewer.

The Ubu collective was established in 1965 and lasted until Thoms co-founded the newly formed Sydney Filmmakers Co-op in 1969. While generations have passed since the historical period under examination, the documentary is an important reminder of the way in which Australian cinema has embraced – and still can embrace – radical notions of production and distribution.

Senses of Cinema

The 1970s was a period of immense social and political upheaval, including land rights for Indigenous people and greater equality for women. The filmmaker co-ops were not excluded from this political legacy. While men like Thoms flaunted the role of nudity and freedom of expression, the documentary illuminates the way in which feminists within the co-ops felt his stance was objectifying and sought to undermine this.

Hughes comments that the persistence of the dominant powers is like how the “historical avant-garde is a form of immunisation. It’s like a jab that the dominant culture uses to sustain its rule.” This lack of cohesion and homogeneity is what is most striking about the documentary and indeed the era.

Although the film covers a lot of ground documenting Sydney and Melbourne’s rise and fall, Hughes still admits there is more work that could be done. In discussing the major cities, he also admits that the Brisbane and Fremantle scenes still need further research. I ask about the omission of a director like Tim Burstall, given how distinctly Melburnian his films appear to be; Hughes responds that the co-ops were “community-based operations [so] they weren’t dedicated to professional advancement. They had a more collective orientation.” Directors like Burstall had a professional ambition, although they did associate with the co-ops.

Mark Hartley rewrote the narrative of Australian cinema with his documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild and Untold Story of Ozploitation! (MIFF 2008). Globally, this documentary suggested to audiences that genre cinema and B-films were championed and pioneered in Australia. However, Hughes’s documentary finds itself positioned in the same period and in the same cultural climate, but without reference to this account. Addressing this, Hughes comments that, during the 1970s and 80s, “it was like a hangover of the old great divide between high art on the one hand and popular art on the other”. This explains the lack of any discussion of Ozploitation cinema while figures like Albie Thoms, Gillian Armstrong, Gillian Leahy and Stephen Wallace feature prominently.

Senses of Cinema focuses on the different strands of progressive politics that Australian cinema and culture are indebted to. When asked how he would like young filmmakers to react after seeing the film, Hughes emphasises the role of the film to “establish the practice of an Australian cinema historiography that is alert to the radical strands”. His words complement the way I feel after watching the movie.