Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks – Q&A with director Serge Ou

From Hong Kong to Hollywood, the Shaw Brothers to The Matrix, iron fists and kung fu kicks have been busting box offices and breaking barriers since the 1960s. Serge Ou's film Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks is the wild story of how the way of the dragon became a global phenomenon. Here, he talks to MIFF about the genre's global appeal, its problematic and progressive histories, Australia's small but important place in kung-fu cinema and much more.

What attracted you to Hong Kong cinema and the Kung fu genre? Do you have the same nostalgia for these films as many of the subjects in the documentary?

I remember the whole Kung Fu pop culture explosion. When I was a child, my first GI Joe had “Kung Fu” grip – a must! I was the 90-pound weakling in the ads on the back of comics that promised reinvention through kung-fu. My dad and I watched the Kung Fu TV-series religiously (yes, I was Grasshopper). And just like Alien Ness in the film, I collected the trading cards and still have them in a box somewhere under the stairs. How could you escape Bruce Lee at the time? I made some rubbish nunchucks that fell apart, realised I was not a kung-fu hero and traded them in for a pair of drumsticks.

It’s just that I love pop culture and all those films from Hong Kong are incredible documents of a genre. Aesthetically beautiful, quirky, fun and, on occasion, confronting. When I first saw those Shaw Brothers films, a new world opened up. For their time, they are impeccable examples of craft, talent and escapism and there really isn’t anything quite like them.

The youthful energy and appeal of these (sometimes quite violent) action movies is one theme of the film. Could you expand on the political dimension of kung-fu cinema and what kinds of audiences they attract?

The films are most often the simple structure of “the hero’s journey” – a character goes on a quest, is confronted with some form of crisis, overcomes it and is transformed. This theme has resonated throughout the history of storytelling, and it’s a narrative arc that resonates in particular with so many disenfranchised and marginalised groups and individuals.

What’s even cooler is you don’t need a gun or an army – just a dude with two bare hands to take on injustice. How could you not be interested?

The film features some shocking moments of cultural offence and appropriation in documenting Hollywood’s history of yellow-face. What does contemporary American kung-fu cinema look like today – has it learnt from this history?

It’s hard to comment as I’m a white man with a Chinese surname! In this age of global social comment and criticism, it’s harder to slip it past the public. Someone somewhere is going to peg you in cyberspace (yes, I’m waiting …).

There’s been some criticism of yellow-face episodes in recent contemporary cinema – Ghost in the Shell etc – and there seems to be a push to redress the issue. For instance, Bruce Lee’s daughter Shannon’s Warrior series, produced with Justin Lin (Fast and the Furious), is faithfully based on Bruce’s original ideas – distorted and some say stolen by the 1970s TV Show Kung Fu starring David Carradine. And Marvel’s announcement of the Shang-Chi (Master of Kung Fu) movie – helmed by and starring Asian-American talent – is, I think, an attempt to address Asian inclusion and representation issues in mainstream Hollywood movies.

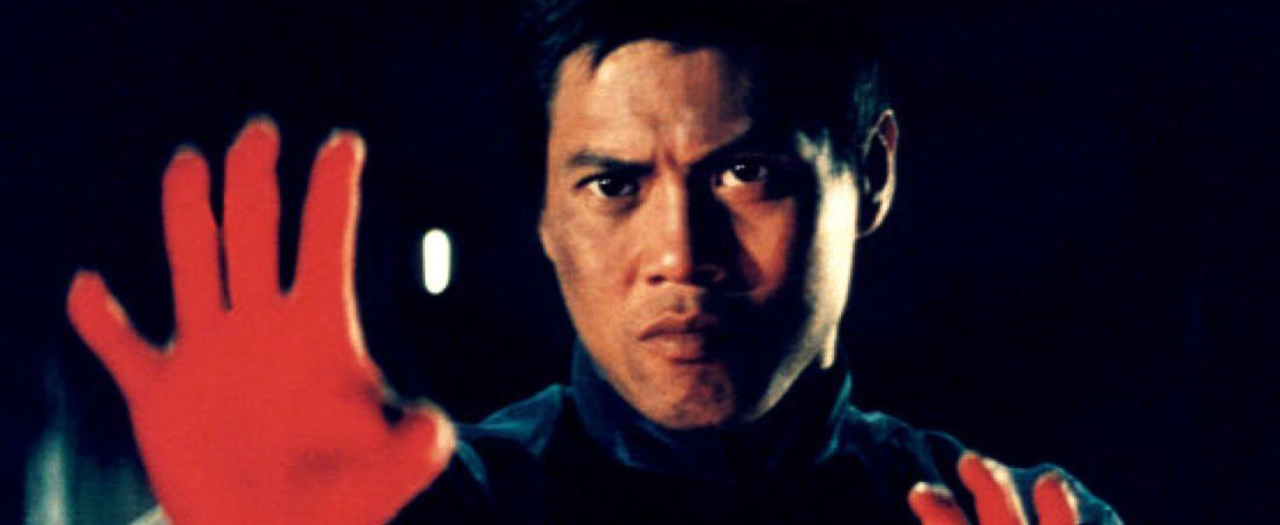

A scene from Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks

The history of the Shaw Brothers studio is a fascinating part of this history and the filmic interplay between eastern and western culture. How have the conditions for making and distributing kung-fu films changed in the era of youtube, social media and streaming?

Interestingly, the Shaw Brothers took the American studio model of the 1930s, 40s and 50s, giving the genre a film factory that functioned through traditional distribution mechanisms. And those films were presented back to the west and resonated.

Now you can talk to anyone, anywhere – and anyone willing can now make a film of reasonable quality. What we see today are more risks being taken, more visceral action, a DIY sensibility and a range of voices, which is really exciting. We’re seeing the genre interpreted all over the world, from Africa to Afghanistan, from eastern Europe to India. And these films are moving through the world online, making them more accessible. But, if you want to see big-budget fare, China and Hollywood are still the drivers.

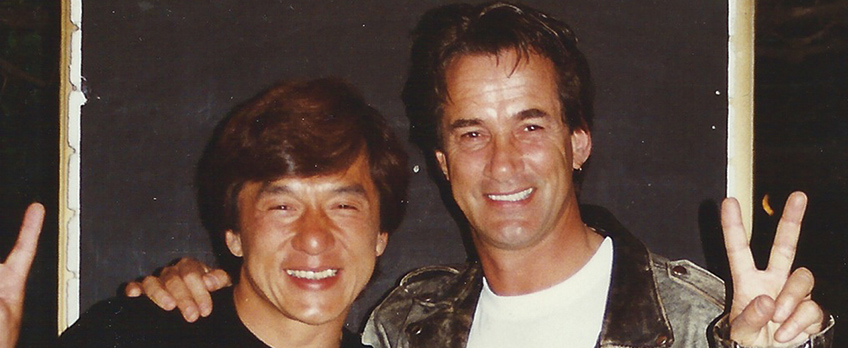

Richard Norton and Maria Tran are two Australian martial artists that have played an integral role in this history – what other contributions to the martial arts genre have emerged from Australia?

Brian Trenchard-Smith really has to be acknowledged for making The Man from Hong Kong in 1975 – the first Hong Kong/Australia co-production kung-fu movie. The film continues to be a cult favourite and a very un-PC document of the time! Also, if Jackie Chan’s parents hadn’t moved to Australia and left him in the Peking Opera School, would he have been a star?

A scene from Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks

Despite action cinema often being cast as a genre with very masculine appeal, your film shows how women have played a key role in the history of kung-fu cinema. Could you expand a little on how gender has been constructed and subverted in these films?

Inadvertently, it seems, Hong Kong cinema set the bar for the modern female action star. But that’s a great thing. Cheng Pei Pei, Angela Mao and other Hong Kong women performers were ferocious protagonists. Just watch the films. And Cynthia Rothrock, the original Atomic Blonde – it was so cool how someone who looked so unassuming could be such a force to reckon with.

Actors such as Sigourney Weaver, Kate Beckinsale, Angela Jolie, Uma Thurman, Charlize Theron, Scarlett Johansson and Daisy Ridley – the list goes on – have all portrayed strong, resilient ass-kickers in contemporary action films. I think they all owe something to those original Hong Kong female action stars. Let’s hope the tradition continues.

A scene from Iron Fists and Kung Fu Kicks

The influence of Peking Opera, ballet and theatre lends a distinctly heightened sense of camp to the genre. How do you imagine this will resonate with contemporary audiences who might be experiencing the genre for the first time through your film?

Go with it. From our contemporary perspective, they may seem a bit camp, but they are aesthetically gorgeous. Sure, there’s a bit of stuffy tradition in there (2000 years of it), but the films – Shaw Brothers especially – are cinematically sumptuous and portray extraordinary physical performances.