Time Bomb Y2K – Four Ways

The live-editing workshop is an integral part of each year’s Critics Campus, and this year, four members of the cohort were assigned Marley McDonald and Brian Becker’s debut documentary Time Bomb Y2K. After penning their reviews, the participants sat through an intensive revision session with Kill Your Darlings Editor Suzy Garcia. Read their final reviews below.

By Lauren Collee

A global disaster is coming, the experts warn, and we have to take their word for it. When the scientists first rang the alarm bell, the crisis was 20 years away – by then, the CEOs would be comfortably retired, so what would they care?

This narrative, familiar to us now as we live under the spectre of climate disaster, could also describe the now widely ridiculed panic that unfolded in the late 1990s. Brian Becker and Marley McDonald’s documentary Time Bomb Y2K assembles found footage to chronicle the confusion surrounding the so-called ‘millennium bug’ leading up to the year 2000. There is a painful temporal specificity to its footage, which is suffused with the naive dagginess of the era – as when a mop-topped Steve Jobs describes a computer as “a bicycle of the mind”. But its portrait of this world, in which survivalist planning jars with a ‘leave no man behind’ philosophy, also mirrors the existential anxiety we face in the year 2023.

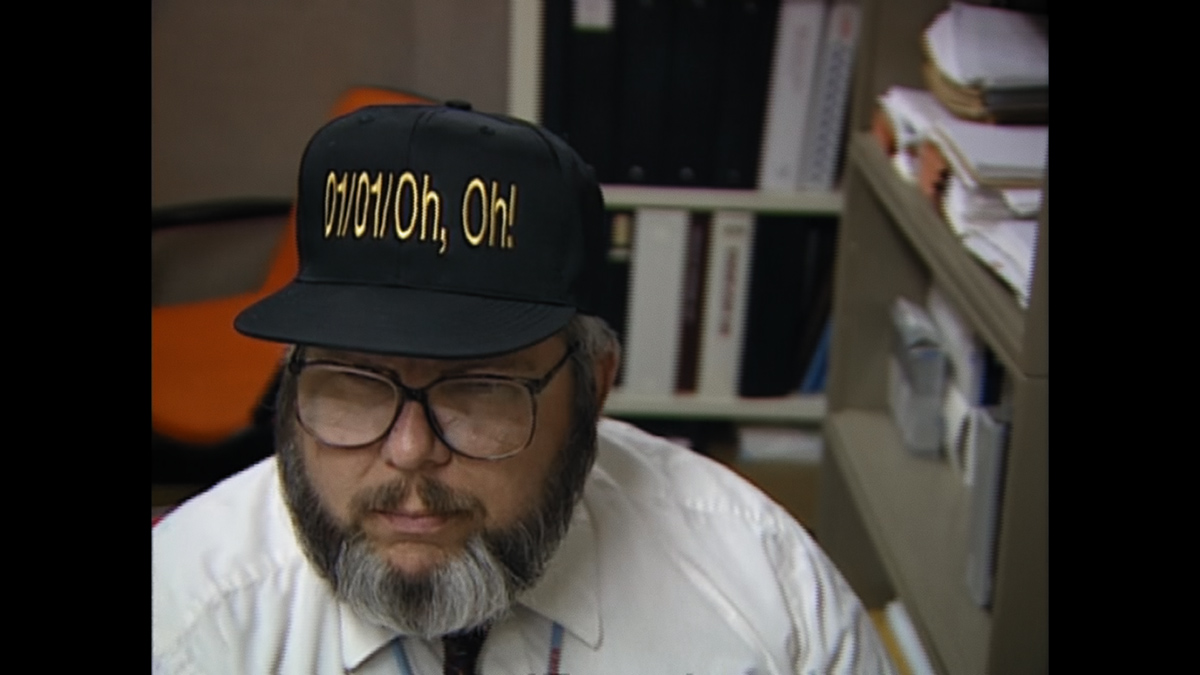

With sharp comic timing and a snappy pace that sets up debugging as a race against the clock, the film doesn’t dwell too long on any single character – though there are recurring faces, including John Koskinen, chair of the US President’s Council on Y2K Conversion, and former IBM employee Peter de Jager, whose opportunistic doomerism is painted in a less flattering light.

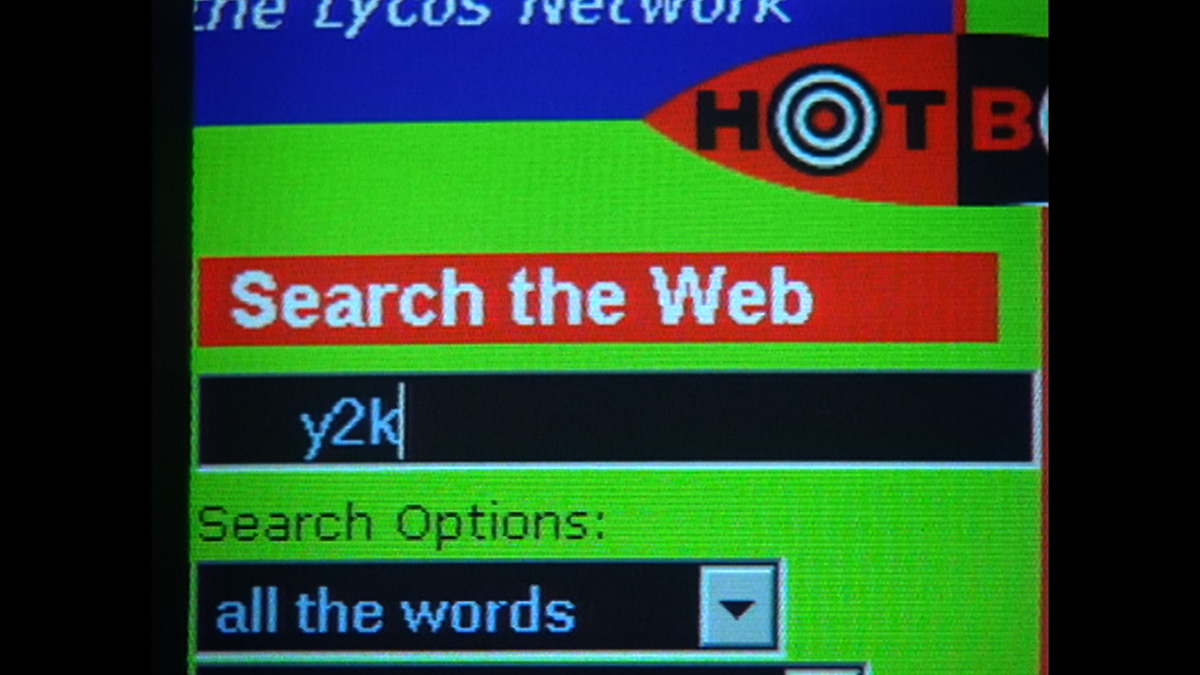

At points, this freewheeling approach comes at the cost of a deeper dive into fascinating and underexplored elements of the Y2K scare, including community preparedness groups that anticipated the resurgence of mutual aid during COVID-19. There are some easy laughs in dredging up the period’s sense of its own modernity, but Time Bomb Y2K also depicts a time in which the internet’s erosion of our social fabric was interrogated with a lively scepticism and not simply accepted as a necessary evil.

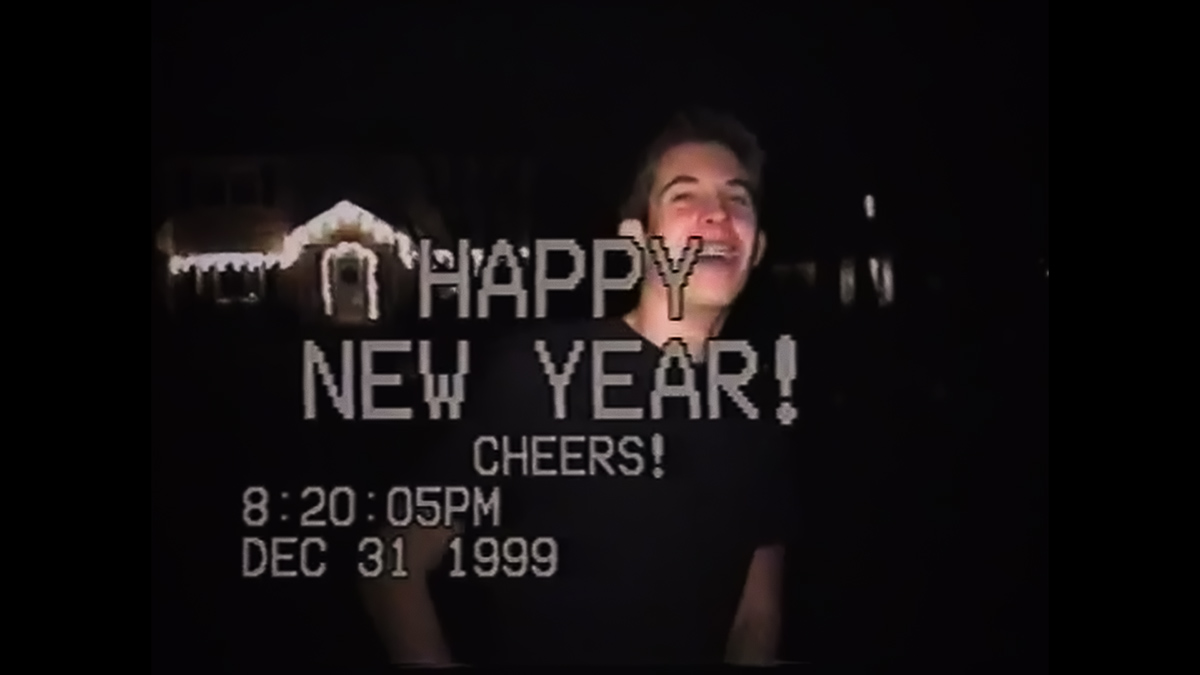

Y2K saw human ingenuity apparently triumphing over the threat of impending chaos. It unfolded in the aftermath of another averted crisis – the successful phasing-out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) from consumer products, thus mitigating the hole in the ozone layer. On the eve of 1 January 2000, a security guard congratulates the Times Square revellers on being the “best crowd ever”, and people roll gleefully on the ground as saxophonist Kenny G performs a lilting, inebriated rendition of ‘Auld Lang Syne’. Whether the fears were overblown or the response was sufficiently comprehensive, the threat had passed, and the world faced the clean slate of a new age.

It’s a familiar narrative structure: things seem really bad, until they suddenly get better. People have a “need for climax”, says one Canadian TV presenter. Read as a documentary that simply chronicles the Y2K panic, Time Bomb is nothing special. But the film isn’t just that; it’s also a tacit statement on our climate anxiety. And this time there will be no clean slate, no midnight jubilee, no fairytale moment when everyone can clasp hands and say we did it – it’s all over now.

Time Bomb Y2K

By Eric Jiang

A single second has never felt so catastrophic. In Time Bomb Y2K, a documentary consisting entirely of archival footage, the anxiety of the clock ticking into the new millennium exceeds the negative technological implications. An impressionistic collection of distresses that people felt at the end of the century, Time Bomb Y2K is a stylistic triumph; but by restricting the film to archival media footage, directors Brian Becker and Marley McDonald limit its scope and impact.

Clips of tech founders (Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, all with incredible hair): from 1996 kick things off: over an insistently optimistic score, they extol technology’s power to unambiguously improve our lives. But it’s not long before we’re introduced to the possibility of the world falling apart because of a pedantic error: computers have been storing years using two digits instead of four. This creates a technological glitch that some think could lead to catastrophe. We see reporters worrying that planes could fall out of the sky.

The documentary then barrels through to New Year’s Eve 1999, skating over a variety of moods and subjects. These scenes are always engaging, and Time Bomb Y2K never allows us to feel bored by following any person or group for too long or in too much depth; we stay with a given subject to capture some specific anxiety before moving on to the next. Memorable episodes include a moment of intrigue when it's revealed that one of the loudest Y2K-bug proponents, Peter de Jager, is massively profiting from speaking fees; and another in which survivalists show off the new, self-sustaining communities they have prepared to occupy in the event of a disaster.

But these moments come and go without much consequence. It would be fascinating to return to these groups after a non-disastrous New Year’s Day, but the film isn't interested in discovering whether their anxieties have dissipated or have been redirected. The film encourages us to laugh at these people’s very real fears, which we can only do with the knowledge that everything turned out okay in the end. It makes the film sometimes feel unempathetic – a dispassionate treatment of people who were distressed and potentially vulnerable.

Nevertheless, the film captivates with a boundless energy, jumping from one thing to the next. It also feels aesthetically pleasurable to feel immersed in the janky digital interfaces of yesteryear, and delivery styles of television news packages that have become less common nowadays. But while the style works, it doesn’t entirely support the substance. When considering the selected archival material used in the making of the film, one might wonder about what was left out by the media of the day; the role of news television on culture; and why what was essential to communicate to the public of the late 1990s is worth showing to us now.

The documentary is essentially a collection of media responses to Y2K, lightly shaped by Becker and McDonald to emphasise the potential of collective action. But details are left out. No interviews with workers who were part of the coordinated effort to solve the problem are ever shown onscreen, and the film never revisits the communities that formed around these shared stresses after Y2K. It all feels too vague to cohere into something memorable or interesting beyond satisfying a surface-level curiosity. Despite its exuberance, Time Bomb Y2K never convinces us why the lead-up to this particular year still needs our attention.

Time Bomb Y2K

By Charles Carrall

“It was all kind of embarrassing after it was over, and nothing happened.” This is my mum explaining to me how it felt to live through the turn of the millennium; though it may as well be a description of Brian Becker and Marley McDonald’s Time Bomb Y2K. Playing as a countdown to the year 2000, the film speaks through an abundance of found footage, comprising mostly home videos and media coverage.

For the majority of the film, Time Bomb Y2K takes what is mostly a neutral approach to retelling the lead up to so-called TEOTWAWKI (the end of the world as we know it). Clips of panic-buying survivalists and sober warnings of apocalyptic potential take on momentum as the film hurtles through several years of deliberation and debate. While each piece of footage vibrates with anxiety, they fail to make much of an impression as a whole; their end point is predestined. Spoiler alert: the year 2000 is just around the corner!

While the computer crash itself may not have ever posed any real threat, the implications of widespread panic certainly did. The fears of everyday people are one of the few revelations of the footage, epitomised by a startling statistic in the film: the national spike in gun sales across the United States, which increased by 20 per cent in the lead-up to 2000. How will you defend yourself when total anarchy takes over? As we know, the only protection against a bad man with a gun is a good man with a gun.

Two men emerge as the dominant faces of the discussion: tech staffer Peter de Jager and US government representative John Koskinen. Throughout the film, both become markers of competing agendas. While de Jager urges the masses to prepare for the worst, Koskinen reassures the public that everything is under control – a futile consolation that only serves to stoke the flames of de Jager’s truther conspiracies.

The archival footage in Time Bomb Y2K meanders towards a teachable moment: times of crisis offer us the chance to come together. As the film draws to a close, it dissolves into a melange of home videos whose subjects attempt to moralise the mayhem. Now more than ever, they seem to say, communities must band together to ‘do the work’ – work that is never expanded on throughout the film. Instead, the directors choose to use these sugary sentiments for entertainment.

As a result, Time Bomb Y2K fails to live up to its own name. It’s hardly as explosive as it promises to be. Sorry!

Time Bomb Y2K

By Indigo Bailey

For cultish soothsayers at the threshold of the 21st century, the year 2000 was a rebirth and an exodus – an opening and a void. Densely packed with archival footage, Marley McDonald and Brian Becker’s debut documentary Time Bomb Y2K is a lurid explosion of anxieties, which at once multiply and blur into a single flash.

‘Y2K’ refers to the swelling panic at the turn of the century, responding to the question of whether computer systems would allow for a smooth transition into the millennium. An earnest newsreader explains this fear in tragicomic pantomime, pointing to a ‘19’ etched into a stone slab – a stand-in for the suspected permanence of the first two digits in coding. The flow-on effects of technological failure were speculated to be endless, from split sewerage systems to worldwide nuclear chaos. These premonitions are most potently articulated by doom’s sprightly hype man, celebrity computer engineer Peter de Jager, and intercut with static-shot images of catastrophe.

But Time Bomb Y2K casts its net even broader than this, evoking the turn of the century as a jittery jolt of vague alienation. A panel of teenagers talk lucidly about their love for their neighbours; a mother mourns the loss of her son’s attention to chat rooms. Strangers gather to whittle sticks and strategise about utopia, while others cock guns and swarm end-of-the-world expos. In media footage and hazy home videos, the film’s subjects careen between worry and excitement about the internet’s elusive sprawl – a dual harbinger of interconnectedness and estrangement.

The documentary is littered with questions it does not pursue – about community, distrust in government and the intensifying scope of surveillance. Its cluttered scope swiftly collapses divergent fears and desires into a homogeneous hysteria. Deploying the scornful humour of hindsight, the documentarians return to spooky synths, Family Guy quips and de Jager’s booming frequency, our most coherent thread of human contact.

In this way, Time Bomb Y2K feels both unsculpted and overwrought. Without narration or a clear thematic structure, its editing resembles an algorithmic stream, tapped into the era’s chaos but not its context. This barrage obscures the filmmakers’ omissions, especially their choice to circumvent the political concerns of its fleeting subjects. While embracing an aesthetic of total collapse, the film becomes unrooted from earthly despair.

There are some compelling moments of ambiguity amid the fugue. As Time Bomb Y2K hesitates on footage of council workers clearing the debris of New Year’s Eve at Times Square, one of them gleefully unfolds a cardboard sign heralding end times before tucking it into a garbage bag. There is a brief reminder that the paranoia of the turn of the century has distracted from the ensuing US presidential election. But this dissolves with the onset of euphoric music and dancing bodies celebrating a “successful transition” into the 21st century. In McDonald and Becker’s hands, Y2K becomes a fever dream without history or fallout.