Making Pictures Move: Rob Connolly on Magic Beach

A long-in-the-works screen adaptation of Alison Lester’s classic picture book of the same name, Rob Connolly’s Magic Beach assembles ten animators working in a range of styles to convey the feeling – and imaginative quality – of going to the beach as a child.

Connolly speaks with MIFF Publications Manager David Heslin about the film’s unique structure, how it came into being and why Magic Beach counts among his freest experiences as a filmmaker.

How did you feel about the MIFF premiere [of Magic Beach] and everything that’s happened with the film since then?

The MIFF premiere was beyond my wildest imagination: a thousand kids and their families and performers and Alison Lester in the house. I was just delighted that the film actually worked so well for young people.

There was one mum there holding a kid, and I heard them say to their little three-year-old, “Look!” – and they were looking at the screen – “Look, it’s like I told you! It’s like a big TV!” And I thought: that kid is having their very first experience in the cinema here, right now, at this film.

These things stick with us – it’s formative, right? Another thing I’ve always loved is the intersection between reading a book to child and then watching a film or TV adaptation of it with them.

Alison Lester talks a lot about making sure that cinema for young people, like her books, allows space for the imagination of young people to come up with their own narrative – that we don’t need to necessarily give kids an overwritten, over-articulated story where they don’t have to think. The power of her books is that, between each page, little children have this incredible space to let their own imagination thrive. The trickiest thing in the adaptation structure was: how do I create a film that is very loyal to Alison Lester’s intention with her books?

When did you first come across Alison’s book? And when did you start thinking of bringing it to screen?

I read many Alison Lester books to my children when they were little; we had a whole heap of them on the shelf. Then, Sarah Watt – who made Look Both Ways and My Year Without Sex, and sadly lost her battle with cancer – and I were talking about doing a film together, and she said, “You’ve got to meet my friend Alison.” So I went down to Walkerville with my daughter Kitty, and met Alison, and went to the [real-life] magic beach.

Sarah and I were working on the film together for many years. And then, during COVID, [producer] Liz Kearney and I picked these amazing animators and invited them to animate a different kid from Magic Beach in their own style. We were very much inspired by the experience we’d had on The Turning, and how we could make a collaborative work with other creative people. Building that group of animators was amazing.

The last piece of it was directing the live action and stitching it all together – that happened [last] year. So it was quite an odyssey, this film.

It’s interesting that the book is present in almost all of those live-action sequences in one way or another. Did you always intend to incorporate the book as a physical object in the film?

I’ve still got books from my childhood on my bookcase, and my wife does too, and I think it’s something at this moment in time that I really value. I love the physical material.

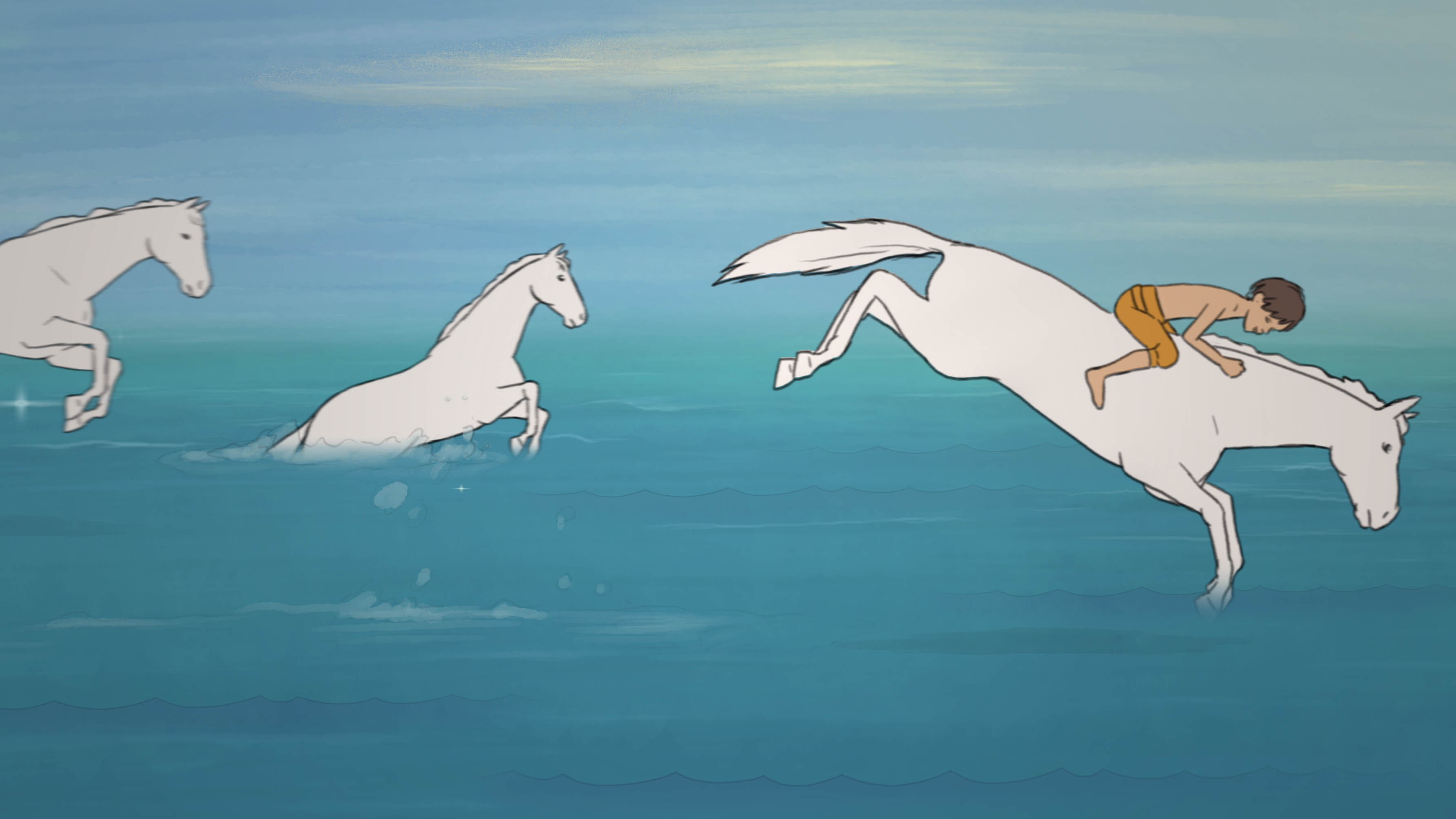

I really wanted to use the book as a trigger for imagination. The film is, thematically, a celebration of the power of our imagination and the magic of the beach to inspire imagination. I think Alison had a great connection to that in her book – the idea that you look into the waves and you think you see horses prancing in them as they’re crashing. So the physical property of that book felt really important to me.

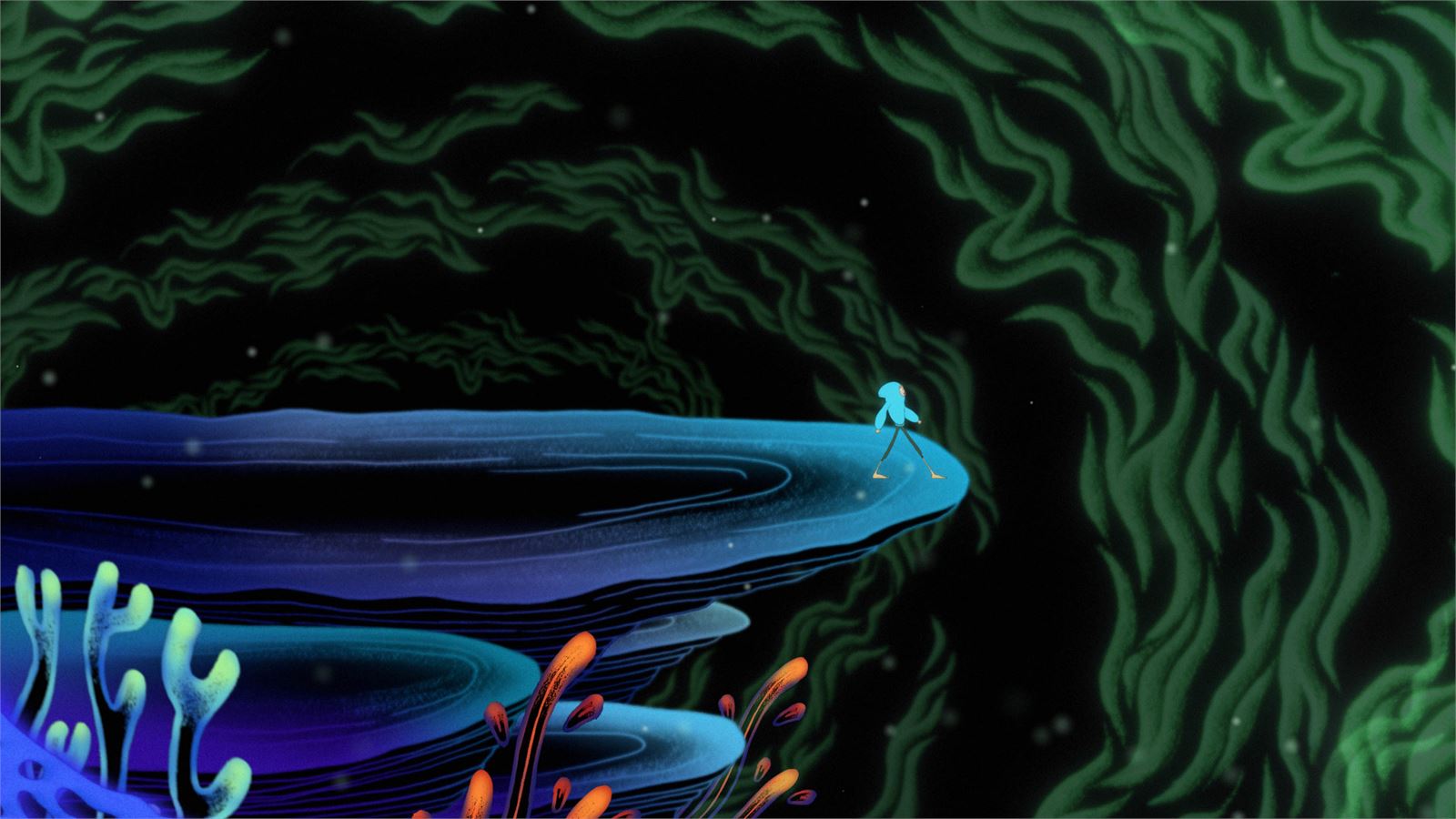

All images: stills from Magic Beach

There’s a quite gentle feeling that’s present through all of the live-action sequences. It’s a very peaceful world that you create.

They’re amazing kids, amazing. We took a bunch of kids between four and seven to the beach Alison wrote it on and then just improvised these dramatic sequences.

On the last page of the book, there’s a frame of a wooden mobile with things hanging on it. When we were down [on the beach], Alison wandered around and made one and brought it to set. And we just came up with the idea of hanging it on the tree and having this great transition where Rylee [Chuck], this young girl who’s deaf and hears the world in a beautiful but different way, is touching these objects. That was what the shoot was like, which might be why it has the spirit you’re talking about.

It wasn’t a rigid script. So much of making films is industrial. It’s so frustrating: you turn up on set, and the script has been broken down into pieces, and you have it organised and scheduled, and you have a completion bond making sure you shoot it all. It’s like an industrial process, when you’re really trying to make film feel like you’re splashing paint on a canvas every day. I got a lot of joy out of the adventure of making the film.

Would you say it’s the freest you’ve felt as a filmmaker?

Yeah, it’s one of the freest times. I always reach for that. It’s a completely different film, but the other time I felt that free was filming in remote parts of East Timor on Balibo, with a very small crew and with local Timorese non-actors, and this beautiful filmmaking team just trying to work out how we could capture it.

It’s such a challenge trying to work out how to avoid an artificial, constructed feeling in our work. We watch so much drama now on TV; it’s all very structured, and there are turning points, and I can often feel the writers’ room and people coming up with narrative. It’s why I love feature documentaries so much.

When a kid’s first starting to walk, they look like they’ve just learned that if they fall forward and move their legs, they won’t fall on their face. I feel like you can create that sense for an audience, that they’re falling forward and swinging their legs – this sense that the drama compels you forward. And that’s why the artificial construction of narrative is something I was trying to disrupt.

I wanted kids to enjoy it; I wanted it to be a bit crazy, a bit abstract, a bit bonkers at times, a bit weird and wonderful, a bit scary and happy and funny and naughty. I wanted it to have a spirit of early childhood, really – like when no-one’s told you you can’t be creative.

That range is really captured by the variety of animation styles in the film. Did you think from the outset that you might want the animators to work in certain kinds of modes as opposed to others?

In picking the animators, we were trying to make sure that there was a massive diversity – in the same way that, if you listen to an album, you don’t want the shape to all be even. So we picked animators to do different things. We knew that there were some stop-mo people in there, but we also knew that there was someone like Lee Whitmore, who’s one of our greatest animators, who did Bigsy the dog; that’s oil painting on glass. Our ambition was to try and find a diversity of styles and to put it all together.

I’m really happy that the film has a kind of cohesiveness despite the disparate nature of the different animators, that it doesn’t just feel like a compendium of short films – that the form of it allows you to investigate the world and realise that you’re in the different heads of the kids. I’d love to think there was more reason in it, but I think we were just on this creative journey, finding people we loved and inviting them to animate bits of it.

So many films, including children’s films, have this very conventional plot structure of a problem that needs to be solved, or a challenge. But Magic Beach is not really like that, is it?

I just think sometimes we do too much work for kids. We stitch it all together too much; we entertain them too much; we don’t let them experience [a film] and reflect on it and contemplate it. The film’s only 72 minutes long, so I’ve made it as a feature that’s not too long for little kids; but it doesn’t have, like, a kid who’s got a dilemma and a problem they have to overcome and an antagonist. It’s got a bunch of kids and a dog that go to a beach, and they all have profound imaginations there, and they fall into these incredible animations, and it accumulates to this sense of a joyful experience of the beach. That’s what the book’s like; there’s no narrative in the book.

Thinking about filmmaking that’s drawn from picture books, very few films have actually captured the feeling of reading a picture book, which is that often it’s not so plot-heavy as a novel or an adult narrative film, but very much about experience.

I think you’ve nailed it. That’s the challenge of making it – we just weren’t quite sure if it would work until those big screenings at MIFF and the test screenings we had. I think the film casts a spell over little kids, because they get used to the rhythm of it.

I feel like in my own creative work, as a filmmaker, I’m trying to shake the tree a bit and do things differently. I think TV is a very narrative form, an obsessively plot-driven form that absorbs plot and twists and hooks and the tricks of narrative to keep you engaged and get you bingeing drama and story. But that’s not the only way people like consuming content. That’s the way we like consuming content when we’re at home and we’re tired and we’re flicking through channels; but if you’re in a cinema and it’s summer, and you’ve gone to the movies with your family … I don’t know. I saw Fantasia when I was four or five, and I still remember it, and I’ve never watched it since. I’m 56 now, and I still remember the experience.

Fantasia is a bit like Magic Beach, isn’t it?

It’s an abstract film. When I think back to when I saw Fantasia, there were bits I loved and there were other bits I was a bit bored by, but the accumulation of it was profound. It doesn’t have a traditional plot; and yet somehow it’s one of the great works of animation and cinema.

I took my son to a screening of Fantasia at the Astor Theatre when he was five years old – that was an incredible experience.

I love that about cinema. That’s why Magic Beach is an invitation to parents to go, “Make Magic Beach your child’s first experience at the cinema; go and watch it together; share it together; talk about your favourite animations; go to the beach over summer and think about the film.”

I hope that the film can enter our culture in a different way like the book has. It’s always terrifying as a filmmaker, making these films and putting them into the world. But I know I’ve been very true to something with Magic Beach. I haven’t tried to make a film that I think will be anything other than a film that I would love and that’s inspired by my experience, as a parent, as a child.