A conversation with Jawline director Liza Mandelup

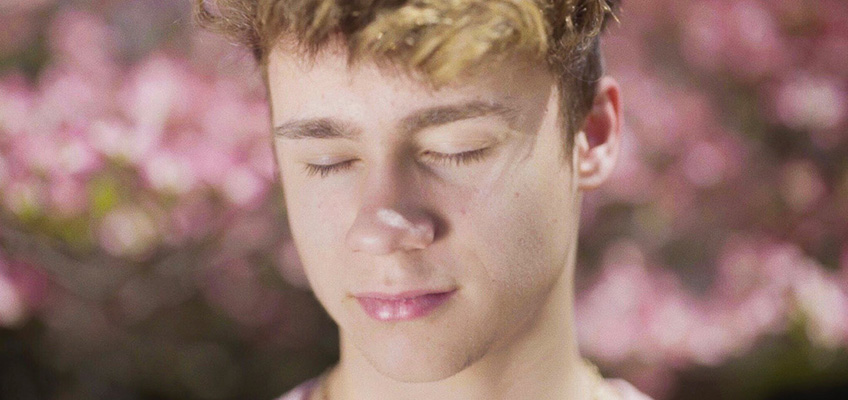

Liza Mandelup began her career as a photographer, and she brings that aesthetic sense to her first feature-lenth documentary Jawline.

“I’m really obsessed with framing and style,” she says. “It’s not good enough just to get the scene. I try to do as many things as possible to make it look cinematic and collaborate with people who work in this space as well. I picture my documentaries playing out like a narrative, but we have all the challenges of chaos working against us. When things actually look good, it feels magical.”

Ask Mandelup her style, and she’ll use the word “dreamy”.

“Everything I do links back to dreams,” she says. “I follow people’s fantasies. Their desires and the emotions behind that – the story elements are one thing and we are always working on that while filming and editing, but that emotional layer is something else that I work on making sure never gets diluted. I care about how people are dealing with their emotions, timeless elements that will last long after the technology in the film has gone. I want Jawline to feel like a teen girl’s fantasy, an all-access pass to intimacy. To the secret lives of boys. But, there’s also a dark side.”

All this beauty Mandelup creates is a red herring. Jawline appears as a pastel fantasy, pretty and pleasant to look at, while telling a more nightmare-ish tale of late-stage capitalism. “We’re gonna paint this fairytale world where people are doing really fucked-up shit. That’s part of the concept behind making Jawline so bright and dreamy,” Mandelup says. “In this world that I’m documenting, everyone’s exploited.”

Mandelup breathlessly lists the ways in which the “boy broadcast” economy impacted the teens’ lives, how kids all over were dropping out of school to sit in front of a computer screen, leaving them ironically more disconnected, less able to relate to the kids in their own schools and towns, and reality. “People want to be spoon fed the hard facts, but I like to show the viewer what’s happening and the emotions involved and let them form their own opinions.”

Mandelup describes showing an early cut of the film to some people. She laughs when she recounts a comment from one that asked: “Does she know how dark this is?”

“Jawline is a reflection of what I saw happening with some teens right now, anxiety and isolation is exacerbated and they’re going to new lengths to cope with it. It’s not just bedrooms painted black. The new teen rebellion is hidden between screens, it’s not as obvious, you have to really go looking into these apps to understand what’s happening here. But if you’re feeling uncomfortable with it, if you’re wondering what the hell is happening, you’re not reading into it. That darkness is there. The first thing I said when I started this film was: ‘This is fucking dark.’”

Girls and Boys

Even though the focus of Jawline isn’t the girls, their voices frame the film. “The girls were more, like, power in numbers. It never felt as though one girl’s story told it all. In the beginning I thought I would have one girl character opposite the boys, but when you notice there’s dozens and dozens of girls feeling anxious, lonely, getting bullied, and wanting to harm themselves, it became obvious they could only be an ensemble.”

Mandelup describes them as the “chorus.” With Jawline, it’s impossible to see the boys without seeing them through the girls’ eyes.

“In this story, the males are objects of desire,” Mandelup says. “This is Austyn Tester’s story, but through the female gaze.” Despite the industry preying upon their insecurities, however, the girls still hold a power that even they seem unaware of, Mandelup explains. They wield the power to mature out of their momentary desire for synthetic love, but until then, Mandelup says, “Ultimately, they decide who is worth sticking around for.”