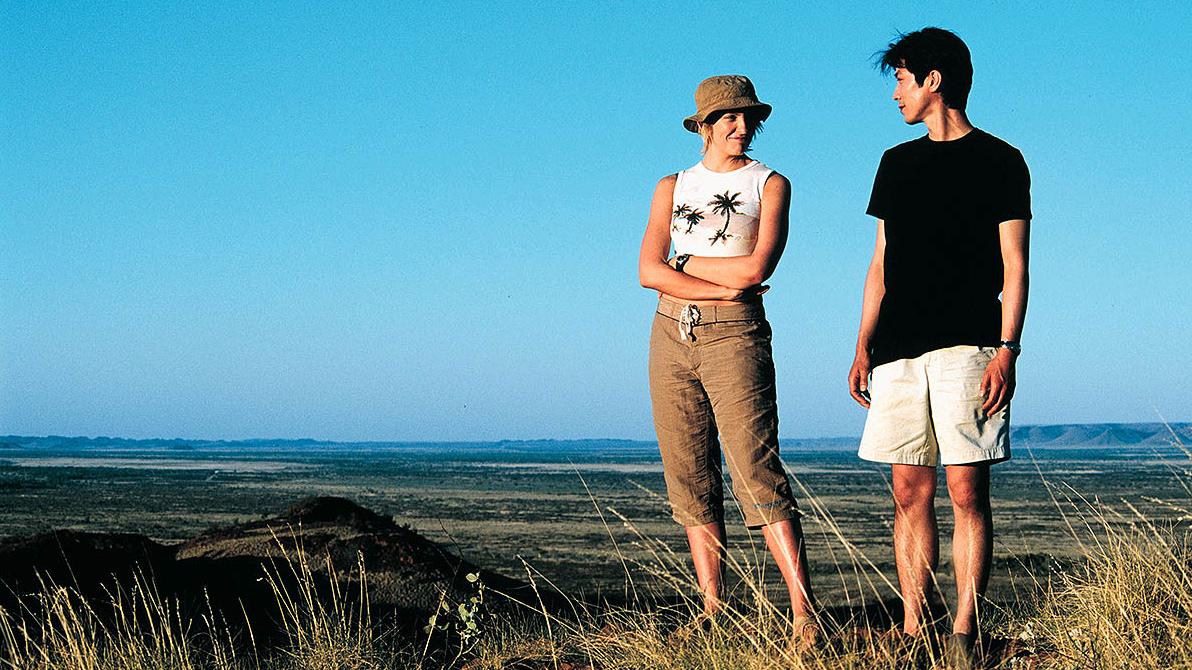

Danger and Poetry: Sue Brooks on Japanese Story

Critics Campus 2023 participant Charles Carrall speaks to director Sue Brooks about the making of her 2003 feature Japanese Story, shooting the film in the Pilbara and Toni Collette wearing pants.

I guess I wanted to start thinking back to 20 years ago, when you first saw the script. The film declares itself as a Japanese story. And I guess I really want to speak to you about that choice – what makes it a Japanese story as opposed to an Australian story?

Well, I guess it’s called Japanese Story [2003] with a little bit of a nod to [Yasujirō] Ozu’s Tokyo Story [1953] – there’s a bit of a reference there to amazing Japanese cinema. And it was called Japanese Story because it was Sandy’s [Toni Collette] Japanese story: it was this story in her life that happened, and it was her Japanese story. Now I feel – and probably [scriptwriter] Alison [Tilson] does as well – slightly different about some of the things that we were doing then, that you might not do now. She was trying to set up all of these cultural stereotypes at the beginning, and then trying to have the characters break that down in the process of the film. So a lot of that is deliberately underlined, hoping that the audience will go with you and then come out and see that those characters have actually shifted immensely through those walls.

There has to be a reverence for the audience and a hope that they’re going to come at it with good faith. It’s a noble pursuit to try to collapse those walls.

It’s always been a question for us [from] way back, from when we first started making films, a question in terms of feminism and film. Women were always looked at, not doing the looking. Yeah, all of those feelings informed where we arrived when I was interpreting the script.

I really enjoyed seeing the Pilbara. I think that you captured its dark sensuality. As Japanese Story is a film that focuses on the treachery of isolation, what was it like to film in that kind of place? And did you encounter the same sort of threats as your characters?

Yeah, you’re constantly aware of it. I mean, I suppose one of the things that we wanted to [put] on the screen was a sense of a truthfulness about that, because the things that we were exploring were the fragility of life and being small spots in the universe. For Alison and I, we really wanted a truthfulness to that. It hasn’t got integrity if you do it in front of a green screen in South Melbourne.

The simulation of it is not the same.

We really needed to go there and really go there. And by really going there, that put us and the film as well as the cast and crew under enormous pressure – like, we had to have three women deciding, “Okay, we can do this,” and we took the film over to the Pilbara. There’s been films made in the Pilbara since then; but at that stage, there hadn’t been. And we had been there [previously], but that’s another thing from actually taking everybody there and being responsible for their safety and everything. So, yeah, we’ve had all of those experiences of people falling over and hitting their head on a rock or hitting a kangaroo with their car. There was a sense that danger still existed, even though we were careful not to do anything too dangerous – I think that edge is still in the film.

Japanese Story

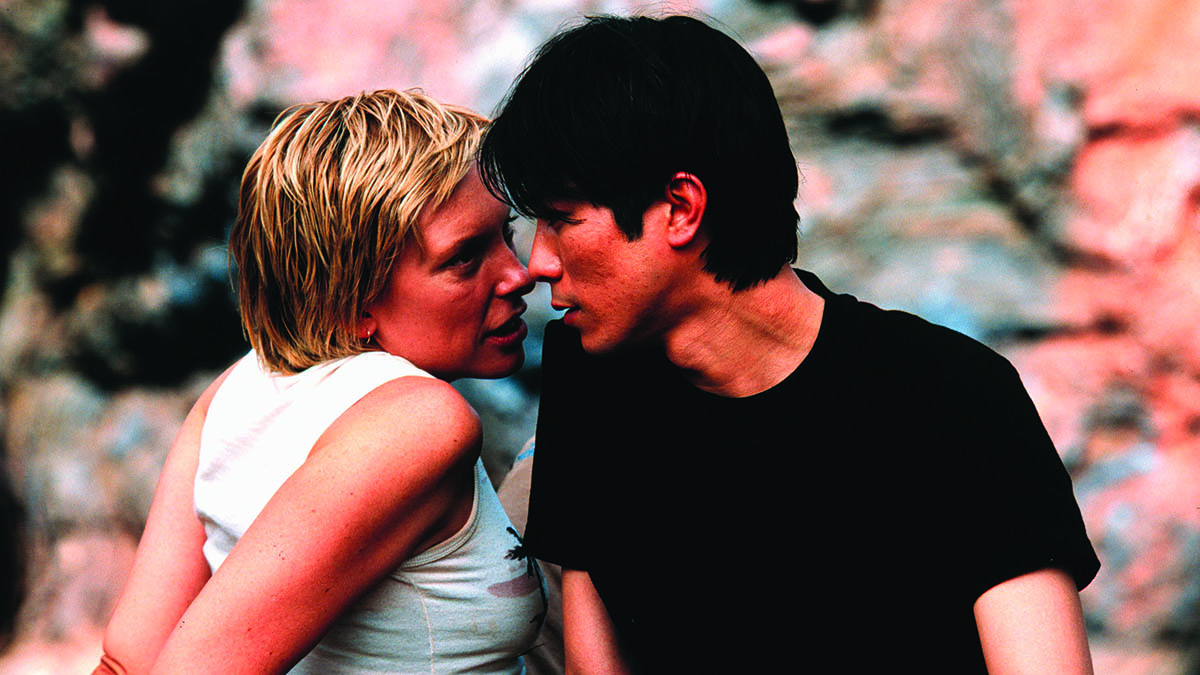

I would love to also talk about a very special scene between Acts One and Two. The scene with Sandy in Hiromitsu’s [Gotaro Tsunashima] pants. It took me totally by surprise. What was the process of choreographing that scene? It’s so singular within the film, tonally, and it sort of brings us into a new chapter of the story.

I think the idea came to Alison one day when she was writing the script, and she was, like, “Why not?” After that, we started to analyse the why not. You could look at it and go, “She’s stepping into his skin” – there’s a sort of slightly animal quality to that, I guess. You could also argue that it’s partly about being feminist filmmakers; we weren’t keen to see her totally naked. I think sometimes there’s that thing where someone writes the thing and it happens in the film, and then, many years later, someone like you [is] watching it. And you’re having a look at it, asking yourself, “What does this mean to me?” That space between an offer and the receiving of that offer – it’s like poetry, a haiku, a bit of a why not moment. And then it became many why nots. Toni wanted to do it; I was certainly happy to do it. And then you’ve got your bit of poetry that just sits, and people take from it what they like.

It’s very transgressive, and I love the question “Why not?” as a dilemma for everyone involved – you know, writer, actor, director. It’s all a different kind of why not, but it’s all speaking to the same culture, wondering how far you can push something. Perhaps we could talk about what this film means to you 20 years on, to have it once again shown at the Melbourne International Film Festival.

It was a great honour.

Looking back at it, how do you feel about this particular point in your career, and this particular film? What do you think prevails from the film? What do you think resonates with you more than it did in the past?

I look at it now and I’m pretty pleased, but surprised in a funny sort of way about how audacious it was for us to think we could do that. I mean, one of the great pleasures of being younger sometimes is that you think, “Oh, why not?” Back to the why not question.

The why not is back.

You think, “Oh yeah, well, we could do that” – and then, slowly, you pull all of the pieces into place, and it supports that. I suppose what I’m trying to say is I love its audacity now. And I mean that not in an egotistical way, just [as] a sort of an observation of looking back at it now.

Totally! And I’m sure you asked yourself the same question when they proposed that you would sit down with me today – you probably asked yourself, “Why not?”

Yes, why not!