Dark Illusions: Niki de Saint Phalle’s Un rêve plus long que la nuit

Critics Campus 2024 participant Isabella Gullifer-Laurie writes on Niki de Saint Phalle’s 1976 feature, a surreal journey into a whimsical, frightening and aggressively sexualised dream world.

She was made of iron, chicken wire, animal glue and painted cloth. She weighed six tonnes and lay flat on her back. She was compared to a whale, a church, a zeppelin, a fertility goddess and a whore. The sculpture, Hon – en katedral (She – a cathedral), was a monumental, multicoloured woman, made by the Franco-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle and first presented in 1966 at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Patrons entered her through a cavernous vagina, a threshold between the folly and pleasures of her colourful exterior and her dark central organs, full of churning gears. The belly, legs and breasts of Hon contained a milk bar, a playground and a cinema. Outside, audio of whispering lovers played; inside was the sound of crushed bottles. In her diary, she once wrote, “The Garden of Eden is right next to Hell. Just a step away.”

Saint Phalle’s 1976 sophomore feature, Un rêve plus long que la nuit (“a dream longer than the night”), continued her lifelong interest in the transgression of boundaries. It was made during the political ferment of the 1970s, with the challenge to sexual taboos and denaturalisation of gender relations finding expression in equally provocative cinema. Films like Agnès Varda’s Lions, Love (... and Lies) (1969) and Jacques Demy’s Donkey Skin (1970) made fantasy and fairytale modes for interrogations of deviant desire and voyeurism, turning topsy-turvy the cultural determinants of the age. Saint Phalle’s film is a tale of whimsy gone tragic, a cinematic dream that proffers a daring disregard for linear narrative.

Un rêve plus long que la nuit opens with a game of hide and seek, a little girl stumbling around a forest. She wears a blindfold, and reaches her arms out to two young men. After eating some birthday cake, little Camélia (Laurence Bourqui) falls into uneasy sleep under linen covers in her pink party dress. She awakes in a kingdom populated by a man dressed in coloured silks and ruled by an enormous dragon; at first, she is horrified by the creature, until it seduces her with its violent nature. Blood spills in beautiful gushes. The scenes of nightmares amass with a nervous rapidity.

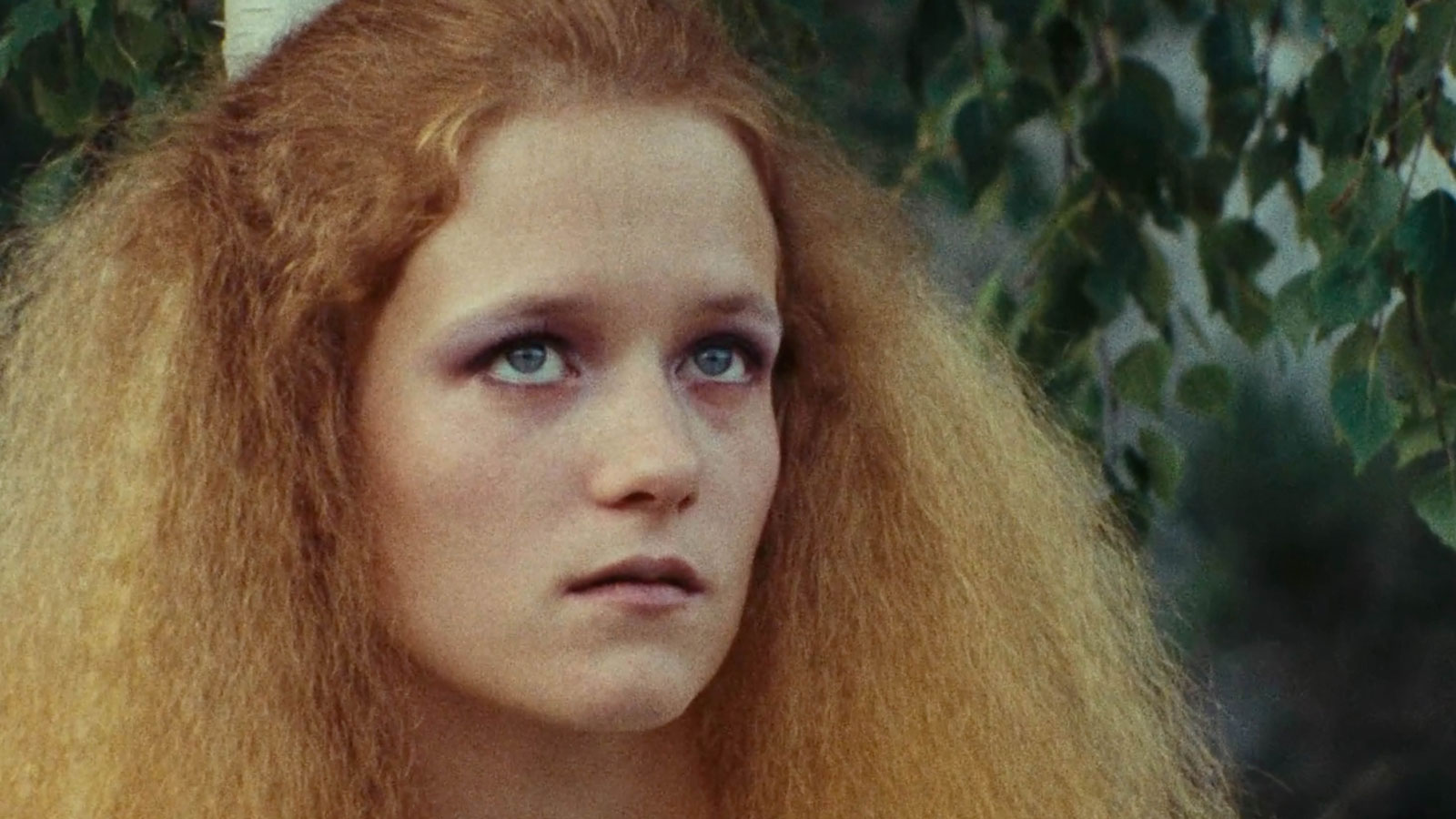

Dreams are a kind of contrivance, a capricious realm ruled by senseless wants and wilful errors of judgement. Midway through the film, there is a fateful dealing of tarot cards. Camélia is transformed into a young woman played by Saint Phalle’s daughter, Laura Duke Condominas. Her ginger hair has the romantic appeal of a Pre-Raphaelite, veil pinned with the corsages of a bride. “I wish to be a grown-up,” Camélia says to a sorceress in a black cape, who replies: “You should know that in the grown-up world there is treasure, if you know how to recognise it.”

Saint Phalle is known for her works that flutter between the innocent realm of childhood and the harsh, sexual world of adults. She was associated with the Nouveau Realismé movement in France, and found early recognition for her Tirs, a series of performances featuring low relief assemblages that held balloons packed with paint. Dressed in a white pants suit and ruff, Saint Phalle would shoot the works with a rifle. Colours splattered like bodily fluids. Later, she developed her sculptures of frolicking women, called the Nanas. Buttocks, breasts and sexual organs found exuberant expression in magnificent scale, vivid colours and exaggerated proportions.

Un rêve plus long que la nuit

Then there was the delirious Daddy (1973), Saint Phalle’s first film (co-directed with Peter Whitehead), an autobiographical psychodrama about a woman extricating herself from the influence of her sexually domineering and abusive father. It includes scenes of incest and masturbation, a giant plaster phallus being caressed and placed in a coffin, a church altar defiled. The monstrous father is joyously killed by a Saint Phalle trussed in a permed wig. She declares: “Mother, I have marvellous news. Finally, Papa is dead.” The score includes a clumsy rendition of Cole Porter’s ‘My Heart Belongs to Daddy’.

Though desires in Un rêve plus long que la nuit are not the unhappy consequence of settling a score, they are still sated by a flight into fancy. Saint Phalle appropriates her sculptures as stage props and scenery, and her illustrated letters and drawings are employed in title cards and animated sequences, each marked by her distinct, curvaceous scrawl. Rapturous, raucously joyful, childishly naive, yes. But these recurring figures of Saint Phalle’s dreamhouses also suggest despair, rage, shame, guilt: suited men slain with swords, the tempting serpent, the monster scaled in green, the many-tongued golem, the devouring mother split in two during birth. Enormous sculptures dominate the dream world, including an immense kinetic structure made by Jean Tinguely, Saint Phalle’s collaborator and romantic partner. It seems as if Camélia has entered the dark guts of Hon – all turning cogs and flying sparks – trailing her skirts through black steel slicked with grease. This is the machine of adult dreams and desires. In Saint Phalle’s hands, the engine is not just a source of energy, a symbol of vitality; it is a hallucination motor, a site of psychoactive dysregulation.

If Camélia entertains childish dreams, she also enters into adult nightmares, where greed, clandestine guilts and crude lusts prevail. The pervasive gloom of the night is disturbed by the heave and crash of cymbals and drums. In scene after scene, she meets petty crooks dealing in death, fascists in vinyl jackets and corrupted priests. These are men driven by paranoia and hatred, who administrate war and desecration, eating children and soliciting perverse sex. With her recourse to guilelessness snapped shut, Camélia enters a brothel, where Saint Phalle plays the procuress, bewitching in blue eye shadow and black silk. She ushers Camélia into her rooms, where a parade of soldiers with papier-mâché phalluses attempt to deflower her. The giant cocks are pleasure machines, violent and silly cannons that explode like fireworks with dizzying sprays of confetti and feathers. As Camélia watches on behind a screen, the trajectory of her naive sexuality becomes a drama of competing desires, between chastity, coquetry and lasciviousness.

The adult Camélia is a spectral figure, an overgrown child shocked into silence. In the final scenes she is completely quiet, eyes shifting back and forth (is that all there is?). If the dreamer’s dream doesn’t satisfy, it needn’t end. Camélia steps out of the last frame in hand with an onyx Angel of Death at sunset. Un rêve plus long que la nuit is a smoky, absurd, dark world, full of cinders and secrets. In her memoir, Saint Phalle wrote, “[My] work and life [are] like a fairy tale full of quests, evil dragons – hidden treasures, devouring mothers and witches, the bird of paradise, the good mother, glimpses of paradise, and descents into hell.” This fidelity to archetypal images offsets the disturbing artifice of her surreal vision. Like a sticky bundle of dirty ribbons, images of sexual rapture and pain are knotted together. Saint Phalle held these things in the balance, her film an arcane script for invention and reverie, a cinema of intuitive sorcery.