Off Country – Q&A with John Harvey and Rhian Skirving

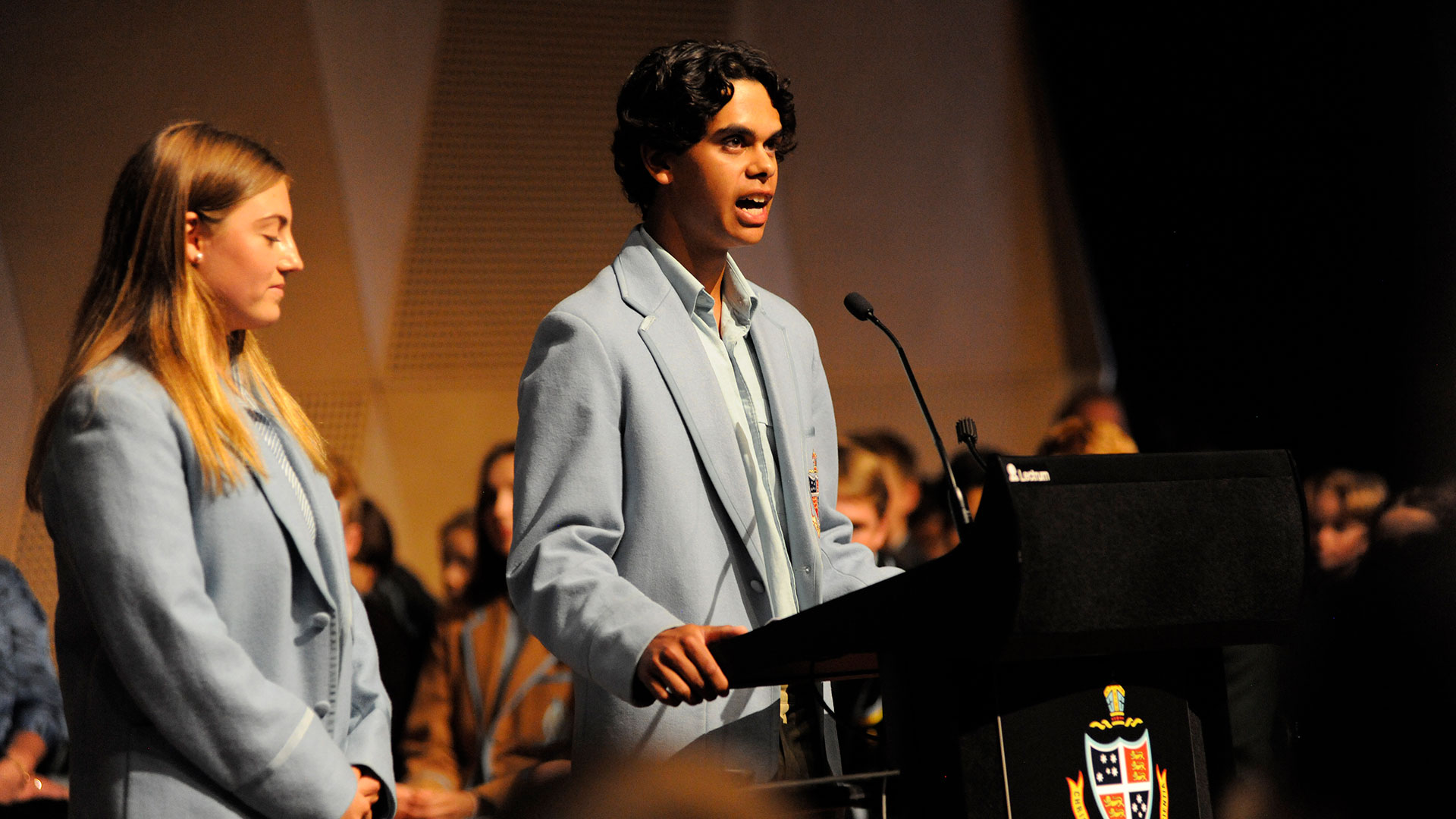

In Off Country, Indigenous teenagers who have received scholarships navigate exams, social dramas and maintaining meaningful connections to home while at boarding school. Supported by the MIFF Premiere Fund, this eye-opening and empathetic film by Rhian Skirving (Rock n Roll Nerd, MIFF Premiere Fund 2008) and MIFF Accelerator Lab alumnus John Harvey (Out of Range, MIFF 2019) captures the tremendous pressures these students face – from academics and extracurriculars to sustaining ties with kin and culture, all of which are further complicated by the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic.

Off Country tackles tough questions around identity, belonging and ‘closing the gap’ for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. What drew you to the boarding school – in this case, Geelong Grammar School (GGS) – as a space to explore these questions?

John Harvey & Rhian Skirving: We were drawn to the boarding school as the setting for the film as a new and fresh vehicle through which to capture the experiences of Indigenous youth. ‘Inside the life of a boarding school’ grabs the attention of a larger audience and allows us to explore issues within an enticing and interesting setting. Institutions like schools provide a good framework for observational films where all the characters are living within one setting, contained within a set timeframe, and their stories cross and interweave. Unless COVID is thrown into the mix, of course!

What were the most surprising revelations for you in making this film?

Just how smart and informed these young people are. Look out in a few years for these kids out in the world. Their ideas and opinions are so well thought through, so mature and delivered with such character.

Off Country

It is so eye-opening to see the adolescent experience captured on screen with such rawness and authenticity. However, this brings very special responsibilities for you as documentary filmmakers. Can you expand on this a little?

Yes, the responsibility is huge and the most important part of the process for us. We wanted to create a structure around the film where the children, their families and the school felt safe. We consulted with the families every step of the way and made all decisions with input from parents, guardians, psychologists and teachers. Having the collaboration as co-directors enabled us to have constant discussion through the filming and right through the editing process. We were careful about the framing of the characters and their family stories for the film, always with an eye on the child’s future self – how they will feel watching themselves years down the track.

And how was it as filmmakers navigating the shoot around COVID? What were some of the challenges you had to overcome?

Well, COVID threw our production model into complete chaos, really. Having set out to capture a year inside a boarding school, we were shut down only weeks into filming, with all our characters sent home. We couldn’t visit them because we were locked down; we didn’t know when school would go back, if at all. Weeks turned into months. Slowly, we were able to get to our characters’ homes; one by one, as different states changed their rules, we would jump on opportunities and grab moments between regional and city lockdowns. Even when school resumed and we were able to get into the school, half our characters could not return due to quarantine rules.

The unfolding pandemic emerges as an unexpected but vital part of the film and has a clear impact on the lives of the students and the school environment. How significant was it for you to capture the experience of the pandemic from their perspective?

COVID, of course, was a very surprising and unexpected element to be thrown at us in the making of the film. But, despite the uncertainly it created, it also led to realisations and story moments we would otherwise not have captured. For example, when Year 10 student Tahlia returns to Darwin and begins attending a local school with a high number of Indigenous students, it made her realise how differently she expresses her Aboriginality in the predominantly non-Indigenous setting of GGS. And perhaps a desire to learn more about her own people in North Queensland and visit country, something she hadn’t had the chance to do living in Darwin.

So, for Tahlia and other families, the long Victorian lockdown gave the students longer at home, and extended time with their families. This allowed families to reflect, and the sacrifices many were making to complete this education were brought into sharper focus. In a way, COVID gave as much as it took…

Relative to the unfinished business of reconciliation, what you would like audiences to take from this film?

In many ways, the film takes a barometer reading of where we are as a country. It’s easy to feel despondent at times, but there is so much to be hopeful for and there are thousands of Indigenous young people across the country who, despite the odds, are showing the resilience of their ancestors and overcoming the barriers in their lives.

Through the stories of the young Indigenous people in the film, we can see how the colonial policies of the past are affecting our young people today. Every family we see is navigating the impacts of these policies, be they the Stolen Generations, forced removal from country, the mission system or intergenerational trauma. The impacts of these policies are present in the children’s lives before they enter the school gate and, ultimately, affect their ability to make the most of the educational opportunity before them. We cannot ignore the impact these policies have had if we want to create a better future for Indigenous Australians.