Making the Festival

The Melbourne Film Festival began as the idea of a few passionate individuals. A sub-committee, formed from delegates to the 1951 Australian Council of Film Societies film weekend, suggested that a small festival of films in the tourist town of Olinda should be held in 1952. The resulting festival was a testament to the do-it-yourself initiative of the Olinda festival committee. As some 800 festival subscribers made their way up the Dandenong Ranges to Olinda – 10 times the expected audience of 80 people – these intrepid film lovers swung into action.

“We felt we had the resources to go and do it ourselves, so we did.”

Additional screens were added, strung up between blue gums in the school yard to make an outdoor screen, and a further venue set up in Sassafras to accommodate the overflow from Olinda Hall. The army were called in to set up a communications system, and the local community called on to help house the film festival-goers, who also bunked down in the local church and school. Such was the popularity of the Olinda Film Festival, and such was the response of its organisers, that the event was a roaring success. From this, the Melbourne Film Festival was born.

Since this bold beginning, the festival has been built on the passion and the dedication of those who make it happen year after year. The organising committees, artistic directors, festival staff, volunteers, and the other dedicated individuals who have contributed behind the screens to put the festival on. These are the people who make the Melbourne International Film Festival, and they have some stories to tell!

A view from the inside

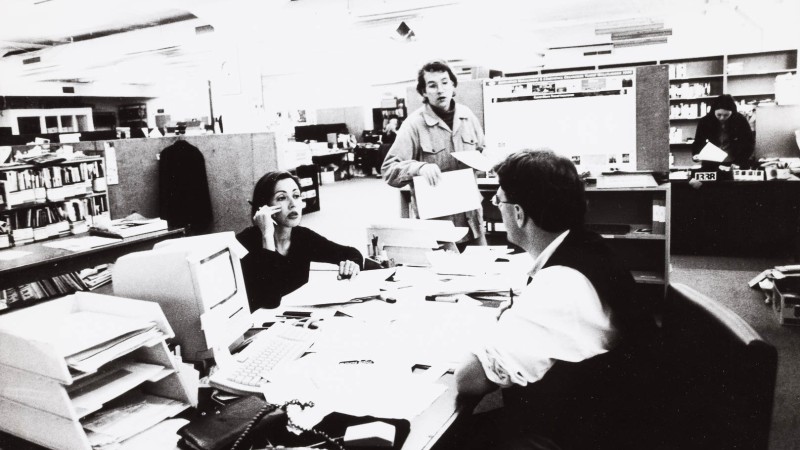

Audiences eagerly await the launch of the festival each year to experience the full event as a glamorous and polished spectacle. Yet the view from behind the scenes can often look quite a bit different. There are the long hours spent drawing together all the necessary resources to see the festival take shape. The joys of watching the final program come together, or the pain when films drop out at the last minute – or fails to arrive in time! There are the ups and downs of organising a live event where success and catastrophe sit uncomfortably close to one another, with the unexpected always threatening to derail well-laid plans.

The stories told by those who have seen behind the scenes are filled with joy and excitement, as well as with exhaustion and anguish for those moments where things go awry. The close escapes where things come together just in time, or the hours of work that ensure that they do. For festival staff who return year after year, there is the joy of connecting with old friends, of the solidarity of wading into the trenches of event organisation, and of battling through to arrive at the end of another successful festival. For the volunteers there is the excitement of a new experience, of trading hours of work for even more hours of film viewing and the joys of seeing how the festival works.

For those at the top, the artistic directors, it is the sense of achievement that comes with each festival edition and watching the event build and grow over time. In its 70 year history, MIFF has only had 12 artistic directors, and they have each left their mark, shaping the festival into what we know today.

Through all the hard work that makes MIFF happen, what remains from those who work there is an enduring love for what the festival represents and what it achieves each year.

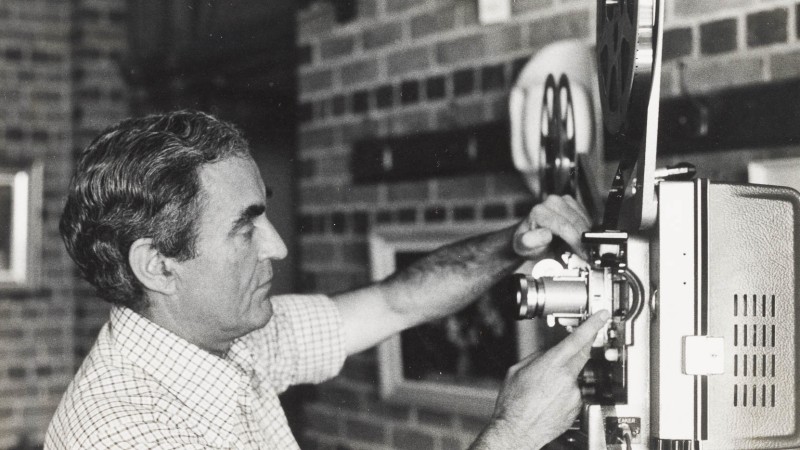

“I did an interview with Gerry Harant, who’s passed now. He and Erwin Rado seemed to be the team: I think Gerry referred to Erwin as the Exec., and Gerry was the fixer. Gerry would sort out their technology, wherever it was, however he could – finding bits of tape and wire to pull things together to make those really old projectors work. They were incredible team.

Dave Thomas was another projectionist. He spoke about going to find lost films. So they would have a film coming in from, I don’t know, Czechoslovakia or Iceland and the [films] would arrive at Melbourne Airport at Tullamarine. And [Dave] would get the call to say the films are here, go and pick them up. At one stage, Dave had sent someone else to pick [a film] up, and he came back empty handed, saying they couldn’t find it. And the film was meant to screen in a few hours. So Dave went to Tullamarine, went to the customs office, and they were looking and looking and looking for this film, but couldn’t find it. And just as he was leaving, Dave saw a big old case, holding open the door at customs. And it was the film! So he picked it up and just ran, ran with it. Quite an extraordinary story.”

“There were cases there like the Mike Leigh retrospective, where I actually helped find a [long] lost film. That was a real buzz. He was probably one of my favourite directors in the world, and he couldn’t believe that we’d found it.

[It was] the biggest Mike Leigh retrospective that ever happened in the world, still. The BBC had done that common thing in the 70s, where they had actually taped over the original video masters [of some of Leigh’s early TV films]. So there was one film that Mike had never seen again, and others that have been found on shelves mislabelled and on videotape and 16mm and stuff like that. But because his early stuff had been for TV, they’d not been seen in Australia, because the ABC had never shown Mike Leigh’s films. So to us, the bar was exclusivity and rarity: just being able to say we’re importing films that you’ve never seen in Australia before.”

“I sometimes like to joke that the longest relationship I’ve ever had has been with the Melbourne International Film Festival. It’s a relationship that began as a punter, then as a member of the media covering the festival, then a MIFF member, then a volunteer and finally on staff for nearly a decade. It’s my home. I met some of my dearest friends while working there. I imagine it’s kind of like those bonds that you forge in a war zone in a way. I mean, and this is maybe something I shouldn’t mention, but it can feel like a war zone when you’re working for it: you’re constantly overworked, under-resourced, never getting any sleep and everything will just suddenly change on a dime, all the time. But you just see that commitment and that love that everyone has for the festival, and we all go over and above to do what it takes.”

“I’ve been a volunteer for a number of years. And wow, that was such a gorgeous experience. Being a volunteer at the Forum meant I got to see behind the scenes, all those secret staircases, and behind the doors of everything; it was fantastic. As a filmmaker myself, there’s nothing I love more then a darkened cinema. And where better to experience the dark than in the spaces behind the cinema and the bio box, in the stairways that lead you to forgotten rooms, to doors behind doors where it was a secret that only people who worked there knew. It was great to explore. It was terrific.”

Erwin Rado – MIFF’s first artistic director

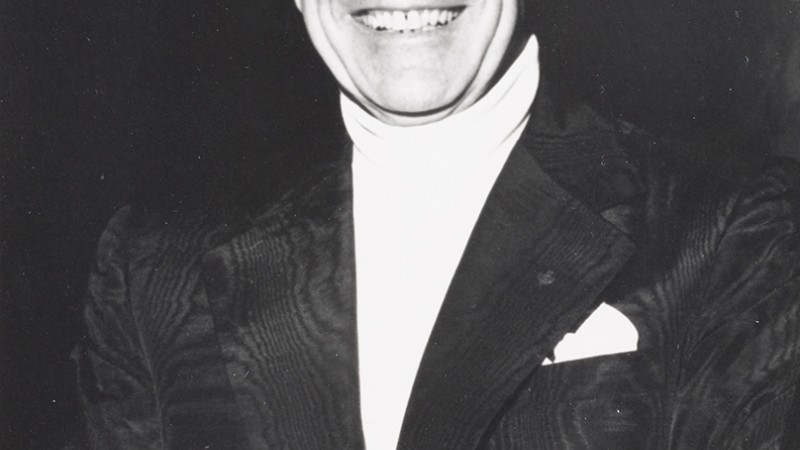

The story of film in Melbourne could not be told without including Erwin Aladar Rado. His influence, spanning more than three decades, and reaching into numerous film organisations – including the Australian Film Institute and Film Victoria – has fundamentally shaped how we watch films in this city. And by far his biggest contribution has been the mark that he made as artistic director for 24 editions of the Melbourne Film Festival.

Erwin Rado was born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1914 to a family of Jewish descent. While his family formally converted to Calvinism in 1920, with mounting anti-Semitism in Europe in the lead up to the Second World War, Rado emigrated to Australia with his first wife, arriving in 1939. Rado was an accomplished pianist and photographer and spoke several languages, including Hungarian, German, French and English. For many, it was his European sophistication and elegance that set Rado apart.

As a member of the Melbourne Film Society since 1950, Rado was associated with the festival right from the start. But his influence only became official when he stepped onto the organising committee following the well-received but financially disastrous Exhibition Building festival in 1953. Within a few short years, Rado had helped the festival move venues to the University of Melbourne campus, been elevated to the newly created role of festival director, helped to establish the Australian Film Institute (AFI), and, through the AFI, secured accreditation from FIAPF (Fédération Internationale des Associations de Producteurs de Films), the self-appointed international festival regulator.

Over the next two decades, Rado would indelibly shape the festival as it moved to the Palais and grew in both size and stature within the Melbourne cultural scene. Rado was a perfectionist to the core, and the festival came to reflect his passion for good cinema. Indeed, the stories are many of his commitment to not only programming what he saw as the best of the world’s cinema but his insistence that audiences show due appreciation to it.

There are the stories of audience members being sent back into the auditorium when they tried to leave part-way through a film. Or stories of Rado racing to the projectionist booth at the Palais when a film’s focus slipped. In his director’s report in 1969, Rado defended his decision not to select Jean-Luc Godard’s film Weekend, noting that “I always regarded the Film Festival as an occasion on which we show top-ranking good films… Despite what has been written about Weekend, I still don’t think that it is one of Godard’s good films”.

For Rado, the standard and expectation for the festival was high. And while this certainly caused frictions and consternation at times with those he worked with, or those who did not share his opinions on “good cinema”, there is no denying that Rado oversaw a golden age of the Melbourne Film Festival.

Rado held the role of director from 1956 until 1979, when he stood aside from the role. He would return for one more year, taking up the directorship again in 1983 alongside Mari Kuttna, before stepping aside once more for health reasons. While Rado passed away in January 1988, survived by his second wife Ann Elliot Taylor, he left a rich legacy through his contributions to Melbourne’s film culture – traces of which remain in the sign for the Erwin Rado Theatre, spied on Johnston Street Fitzroy, or in the annual celebration of the Film Victoria Erwin Rado Award for Best Australian Short Film. And, of course, in the continuation of the Melbourne International Film Festival.

“He [Rado] used to come in and do intros at the cinemas and things like that. I remember talking to him at one stage in the foyer in between films, as he was just walking around, and because he was as involved as anybody could be. He wanted to know what I thought about what was going on in the film. And he’s just this lovely, sort of tall, elegant European gentleman, who sort of held things together in a way that was just really wonderful, because that era was very definitely a sort of a transformational era – from the film clubs up in the hills and people like Melbourne Uni Film Society and things like that. And he just welded it all together and turned it into the fairly powerful thing it is now. And I think we’re all pretty grateful for that. And, you know, he was just a lovely man.”

“Erwin put great faith in FIAPF, in those days the governing body of international film festivals around the world. If you weren’t in FIAPF, you couldn’t call it an International Film Festival. So Erwin would do anything to stay in with them. And one of the dictates was that you had to have a press book with a review of every film. But of course, the press didn’t review a tenth of the films. So there was a little gang of us who used to sit there scribbling away; I used to just write notes in the dark. And then, because there were generous intervals between the films in those days, you’d dash off to the car and record the notes and start a review, then write it up and send it off to Erwin. Although, if he didn’t like what you’d written, it could be quite confronting!”

“There were the kind of abrasive things you hear about Erwin. [But for me] they’re largely positive memories. I was probably over-awed and kind of couldn’t believe what I was doing on the board of something like this. But he was always interesting to talk to. He was lovely to talk to about music. Always smart, always very well dressed. And very friendly.

We often had disagreements on films. Particularly at that stage, MUFS was really venturing out in its taste. We were really an outlier, I think, for bringing the auteur theory to prominence. And some of the directors we were championing were not directors that Erwin was championing. He was very much involved with European, particularly the Eastern European, cinema and at times we had the feeling that the films he was picking were films that were very good politically, or saying very important messages, but there were other films we liked better.”

The fight against censorship

As a festival of the world’s cinema, MIFF has often screened films that confront its audiences. The festival’s programs challenge us to consider different points of views, to witness worlds and stories that push the boundaries of what we think we know, of what is possible, and what is taboo. But what happens when the festival’s films are deemed to be too much and too confronting to screen?

Over the years, MIFF has had its share of run ins with the film censors. This was particularly true through its first two decades, a time when censorship in Australia was notoriously conservative. Films programmed from overseas festivals would often be censored by customs, with scenes of violence, sexual conduct and blasphemy excised from the prints.

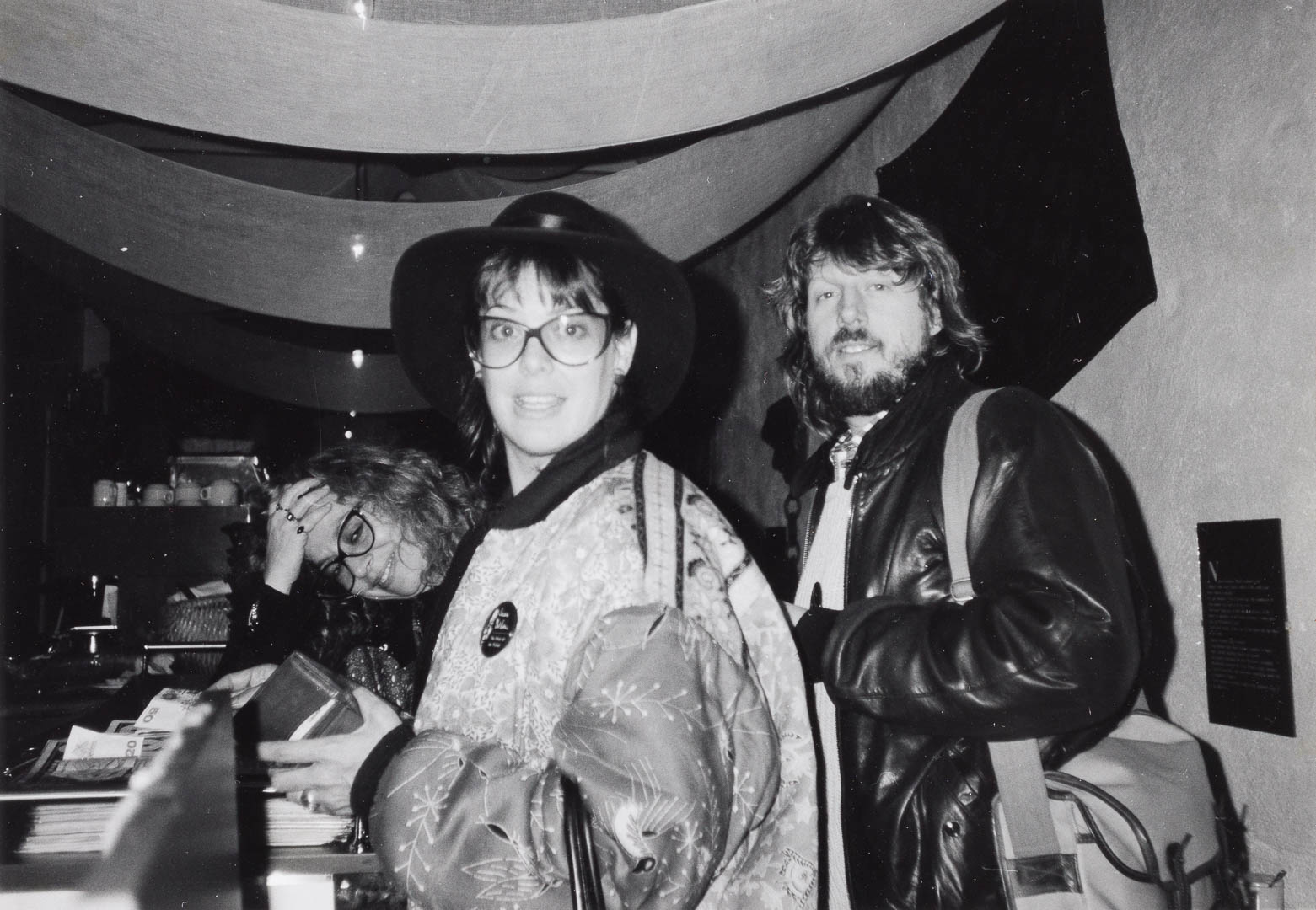

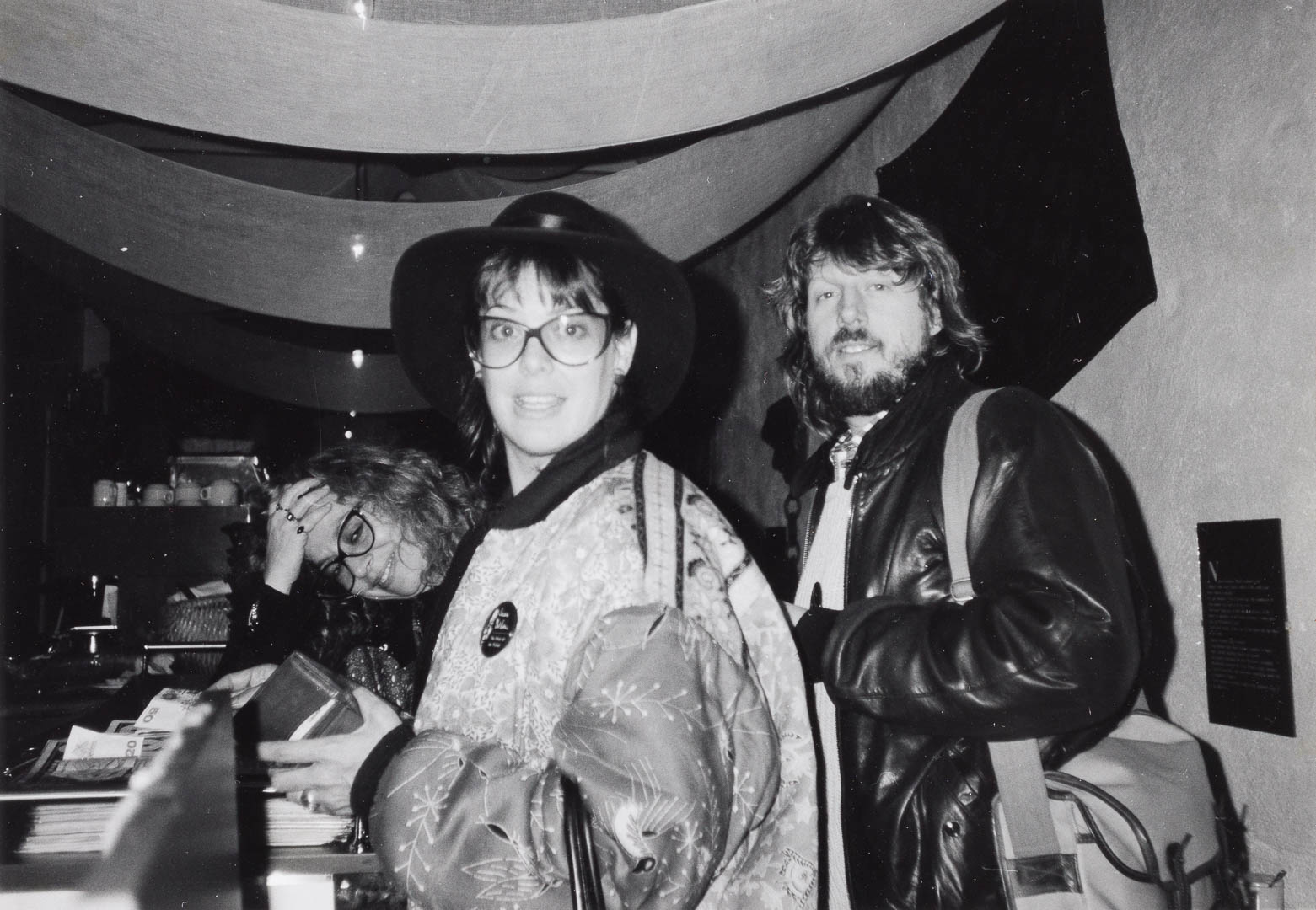

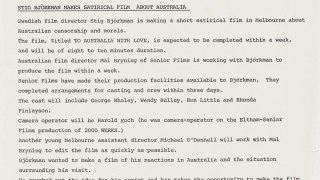

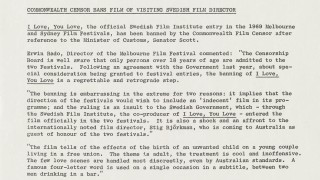

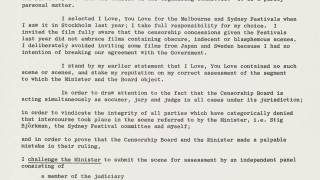

The censorship issue came to a head in 1969, when Stig Björkman’s I Love, You Love was banned from screening at both the Melbourne and the Sydney Film Festivals. The film, which depicted a married couple with a visibly pregnant wife sitting naked on a bed, was considered obscene by the Chief Censor and the Minister of Customs at the time, who assumed the couple were engaging in onscreen intercourse.

Björkman, who had come to Australia as a guest of the festivals, was shocked by the censors’ allegations. Across his press appearances in Sydney and Melbourne, Björkman catapulted the issue of censorship onto the front page of the country’s newspapers. This brought to a head tensions that had been building through the 1960s as David Stratton at the Sydney Film Festival, with the support of Erwin Rado in Melbourne, called for change to the censoring of festival films.

Björkman, for his part, responded in kind to the censors, making the short film To Australia with Love with local Melbourne filmmakers to criticise the government’s censorship. That film was approved by the censors and screened at the 1969 Melbourne Film Festival.

In the wake of the Stig Björkman affair and the publicity it generated, the festivals and film industry won a major battle. In 1971 the R certificate was introduced to enable films with adult content to screen to adult audiences. But while this was a major win for the independence of film programming, it did not completely signal an end to the issue of censorship for the festivals.